Diderot is famous for the creation of the Encyclopédie. A massive, multi-volume work dating to 1751-1772, it highlighted especially the mechanical arts and is often credited with launching the spirit of the French Revolution. Diderot also wrote a short piece critical of luxury in 1769, “Regrets for my Old Dressing Gown” (https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/diderot/1769/regrets.htm).

His arguments are pretty standard and are often heard today: luxury makes people prideful, effeminate, and acquisitive. It is a form of idolatry which dullens sensitivity to the needs of others. Repeating Plato’s charge made thousands of years earlier, luxury points towards the courtesan, and, Diderot adding a nationalist note, English fashions. It is also responsible for a loss of autonomy, coarsening of manners, and debt.

Diderot buys a new, scarlet dressing gown only to find he misses his old, trusty friend: a well-worn, ink-streaked robe. He tells us he looks stodgy in the new when he’d looked picturesque in the old.

He offers an arresting image: the new gown compels a complete overhaul in his rooms and demands that each and every space be filled with other luxurious items. The new gown takes on an agency of its own and re-orders his life. It’s likely not possible to know for sure but his point does recall Smith’s passage on glamour (an old Scottish word for a spell) taking charge of life (Theory of Moral Sentiments, p. 181; cf. V&R Chapter 4).

Underlying Diderot’s complaint is an aesthetics. For Hume, luxury is refinement, which Hutcheson and Smith explain as complexity, i.e. uniformity amidst variety. Smith’s exemplar of beauty is the machine.

Diderot is anxious lest the filling up of his rooms with new luxury items forces out his beloved Vernet painting. Vernet did a number of paintings like the one below: this one is a pretty good match (though not perfect) for the scene depicted in the Vernet he owns and tells us about (Is that one lost?). Diderot lauds Vernet’s painting as picturesque — a favourite term of his — and praises the drama: “true, active, natural, living.” A Tory sensibility critical of Smith’s Whig machine, therefore.

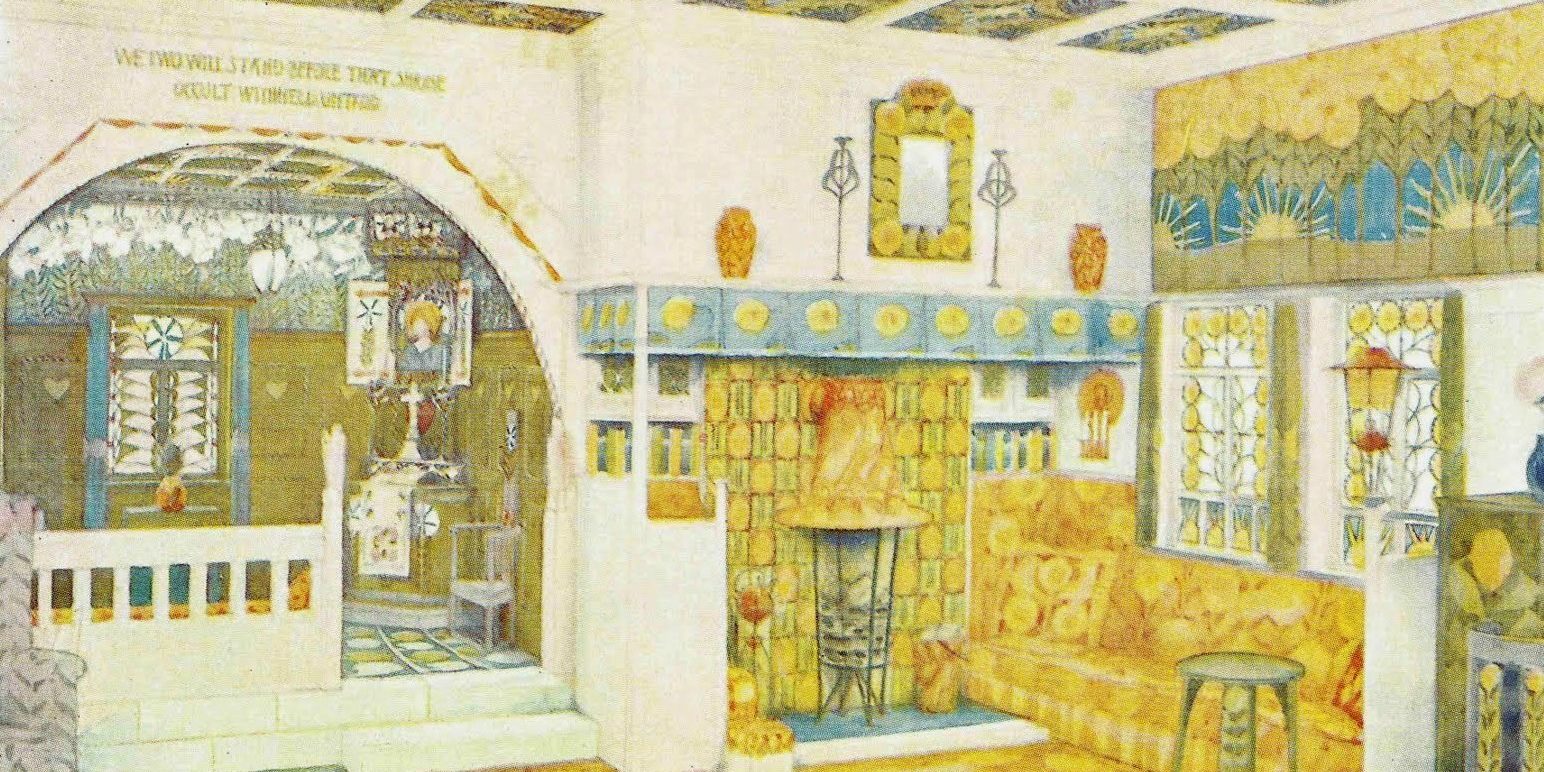

The Vernet depicts the loss of property, the drama standing as a divine reproach to luxury and vanity. This post’s lead picture — an interior by Scotsman Mackay Baillie Scott (d. 1945) — suggests that refined, machine-like interiors of private dwellings can be compellingly combined with veneration (look closer at the Baillie).