Fashion & Power:

Fashion and Power: Agamben and Pryzwara on the Vestments of Power

This book shows that Whig and Tory are reconcilable, that vanity and luxury can, with the right business model, work for justice. This book started with the nineteenth century French anarchist Proudhon and it is fitting that it end with the contemporary Italian anarchist Agamben. His challenge to the thesis of this book is total: the conflict between veneration and refinement, theology and fashion, is no more than a storm in a teacup, a case of sibling rivalry. Fashion, for Agamben, is a species of political theology.

He challenges my vanity, since your author thinks this book carefully and imaginatively addresses a real problem, but Agamben also aims to burst the balloon of designers. If you told Coco Chanel or Dolce and Gabbana that they were doing theology they might not demur but many designers would be mortified.

Oppositional fashion, as fashion theorist Elizabeth Wilson terms counter-cultural fashion, is a staple of what many in fashion think they are doing. Of course, lots of designers do not think politically about their swimsuits or loungewear but some certainly do.[1] Alexander McQueen’s 1995 “Highland Rape” was a commentary on contemporary British politics and an historical event Adam Smith and David Hume both witnessed. After the Scottish defeat at Culloden in 1745 the British government forbade the wearing of tartans. Only Scottish regiments loyal to the British Crown could continue to wear tartan.

2

I do not know what Hume and Smith specifically thought about the Dress Act of 1746. As both supported the Crown,[2] I imagine they were more comfortable with it than McQueen two centuries later. Admittedly, they were no friends of sumptuary laws in general but nor were they sympathetic to the Scottish Highlanders, unlike Adam Ferguson.

3

That the Dress Act of 1746 reverberates 250 years later is testimony to the importance of vestments and power. Hannah Arendt’s seminal Eichmann in Jerusalem opens by her observing the clothing and manner of walk of the judges as they enter the court to try the “banal” Nazi, Eichmann.[3] Agamben wants to layer an observation like Arendt’s, arguing that the West is in thrall to a theatre of clothes, its people diverted by costume, whilst power sits behind that glamour unchallenged.

4

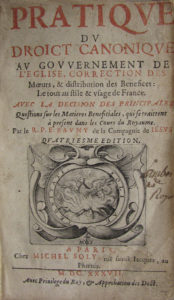

Agamben (b. 1942) is one of contemporary Europe’s most original and widely published thinkers and, startlingly, he is sure that any proper assessment of power and dress in modernity lies “in the dry Latin of medieval and baroque treaties on the divine government of the world” (KG, xii).[4] On account of its emphasis on fantasy, I like the title of Elizabeth Wilson’s fashion theory book, Adorned in Dreams. If Agamben were to write such a book he’d likely title it, Adorned as Angels. He would not be making a pun on the Victoria Secret angels — though that fashion phenomenon is not irrelevant — but following an insight of Carl Schmitt’s that each epoch forges a “metaphysical image” that legitimates a particular form of government.[5] To discern these images of legitimation is the work of political theology. Agamben proposes: “long before the terminology of civil administration and government was developed and fixed [in modern states], it was already firmly constituted in angelology” (KG, 158). Angels are our image.

5

But why should we care about government administration? Isn’t the welfare state our friend? Political theology is not primarily about the idea-worlds of social movements but an analysis of the history of Western political theory. For many, political theology is synonymous with Carl Schmitt. His 1922 Political Theology is a touchstone and Agamben frequently engages with Schmitt. However, as Schmitt himself points out, political theology has its origins in anarchism. Early nineteenth century anarchists were convinced that with the killing of the French king in the revolution only half of the job was done. Crown and altar had governed France and full liberation was only possible once theology’s grip on politics was uprooted. Political theology is a method of exorcism: identify the continuing presence of theological concepts in politics and therewith hold them up to withering critical appraisal. Agamben is the latest in a long line of anarchists attempting this exorcism.

6

Agamben follows French historian and theorist, Michel Foucault, in thinking of politics in terms of biopower and now the connection with fashion becomes clearer: fashion clothes our biology. The modern history of the West, argues Agamben, has been the stripping away of all institutions able to decentralize, diffuse, and resist power.[6] On one side, the state, on the other, populations micromanaged, headless bodies, so to say, related to one another through management metrics. Agamben is fond of the famous frontispiece to Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan: the State, in the figure of a giant man, hovers over a city, its streets empty of people; the city’s residents, with only their backs visible, are embedded in the torso of the man-State (Stasis, 44-45). How is it true that our very bodies are absorbed into the state?

7

Beyond the veil, the reality is that each and every family member is exposed to the total and lethal power of the monitoring state. But how does fashion facilitate this total exposure of the population to the state?

8

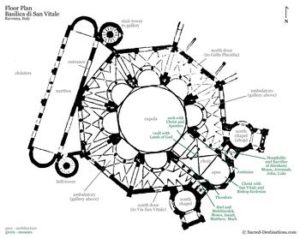

Agamben believes himself to have found a new field of study, the “choreography of power” (KG, 184): the science of “acclamations, ceremonies, liturgies, and insignia” (KG, 188). Agamben argues that the imagistic character of contemporary politics is akin to the liturgy of the Catholic Mass. In each, power (Kingdom) dresses and masks itself (Government) (KG, 168, 256). Whether the Mass or fashion design, we are all now in thrall, declares Agamben, to “the society of the spectacle” (KG, xii). Imagistic politics preoccupies us, seductively wrapping Government, whilst Kingdom hides: we no more practice political self-rule than medieval serfs.

9

The Whig argument that adornments and opulence drive the economy, and Smith’s observations about the spectator and celebrity fashion (KG, 255-56), provides Agamben evidence:[7] “Liturgy and oikonomia are, from this perspective, strictly linked, since as much in the songs and the acclamations of praise as in the acts of the priest, it is always only ‘the economy of the Savior’” (KG, 173, 188). Agamben is fond of a Byzantine ritual manual that speaks of the need to project royal power onto a mirror: central to power is the image (KG, 184). Fascism was masterful at liturgical politics but progressivism is not shoddy either. Imagistic politics, with the cooperation of design, fashion, celebrity, songs, and pop videos, seeks out “consecrated symbols” (KG, 188). For the Right one can look to the “messiahs” of the ’30’s but the Obama presidency has masterfully marshaled imagistic politics: the Katy Perry Obama campaign dress, Jay-Z’s video “On to the Next One,” and the artwork of Shepard Fairy, show that political rule of salvific government trades on the “inseparable brothers” (KG, 285), veneration and refinement.

10

For Agamben, the relationship between Whig and Tory can be summed up as “the Catholic Question.” The urgent task of philosophy is the exorcism of, not demons, but the good angels. This is an undeniably interesting thesis but is the genealogy correct? Massive problems beset Agamben’s thesis. For example, St. Bonaventure argues explicitly that the angels of the philosophers — meaning the Greek and Islamic traditions — administer (Government) but the angels of the theologians rule (Kingdom):

11

According to the philosophers, it is the function of these latter [angels] to move the heavenly bodies. Consequently, the administration of the universe is attributed to them, inasmuch as they receive from the first cause, God, an influx of power which they, in turn, dispense in the work of administration that has to do with the natural stability of things. According to the theologians, however, the ruling of the universe is attributed to the angels according to the command of the most high God…[8]

12

Bonaventure does not feature in Agamben’s genealogy, but the great master of the Franciscan tradition obviously complicates the story Agamben wants to tell. A far greater problem though is Agamben’s constant ignoring of the use of analogy in Christian metaphysics. Erich Przywara has argued with tremendous sophistication that Catholic metaphysics is unintelligible lest attention is paid to the role of analogy.

Agamben’s claim that power (Kingdom) hides behind the ritual, design, and adornments of economic managerialism (Government) assumes a foundational equivocity in medieval Christian theology.[9]

“The economy through which God governs the world is, as a matter of fact, entirely different from his being, and cannot be inferred from it” (54; cf. 59, 64-65). It is the discontinuity between the reality and appearance of authority that gives power its obscure, lurking, menacing quality.

13

If we turn to Bonaventure again, we can readily see this is wrong. God, says Bonaventure, is communication[10] and both creation and the Trinity express God’s communicative being. In Agamben’s terms, Government expresses the communication of Kingdom, and this is why Bonaventure says that the angels rule. Nowhere does Agamben formally address the vast scholastic debates about analogy. The point is crucial: his genealogy collapses if he cannot substantiate the theological divide between Kingdom (God) and Government (angels).

14

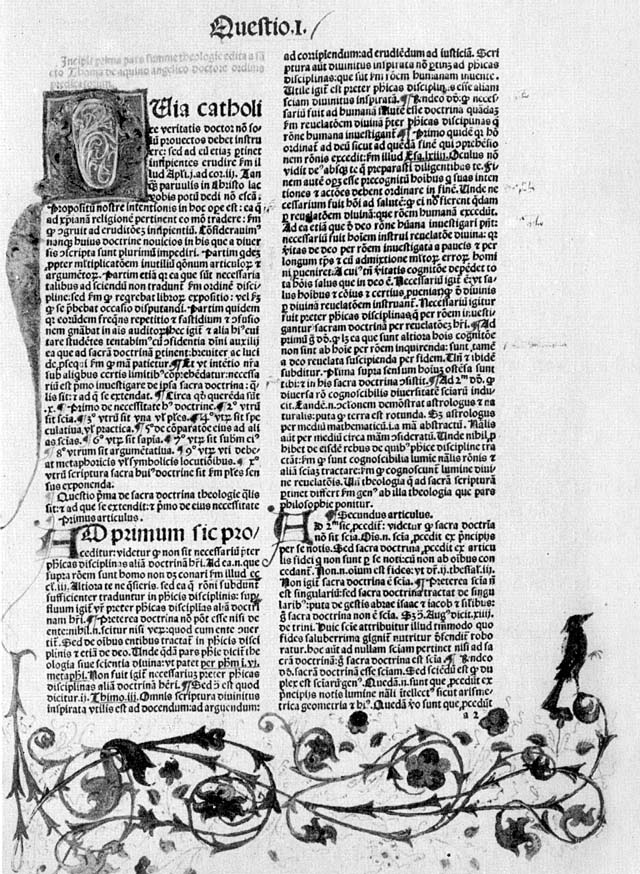

Having mentioned that Bonaventure’s Franciscan thought contradicts Agamben’s history, let me briefly assess whether Agamben fares better with the Dominican Aquinas. Aquinas appears at length in Agamben’s argument. The scholastics themselves viewed Aquinas as only one of a large number of brilliant theologians, but his subsequent role as the foundation of Catholic thinking well warrants Agamben’s close attention. Discussing Aquinas’s treatment of the period’s commonly discussed distinction between God’s absolute and ordered power, Agamben glosses:

… it made it possible to reconcile God’s omnipotence with the idea of an ordered, non-arbitrary, and non-chaotic government of the world. But this de facto amounted to making the distinction in God between his absolute power and its effective exercise, between a formal sovereignty and its execution. Limiting absolute power, ordered power constitutes it as the foundation of the divine government of the world (105; emphasis added).

15

This simply will not do. Aquinas does not for a moment think that ordered power limits God’s absolute power. Ordered power is an expression of God’s absolute power of love, God’s plan for the development of history. And Aquinas says this in the passage Agamben glosses! Immediately above the gloss, at the end of a long quotation from the Summa theologiae, we read Aquinas’s own words: “Accordingly, we should state that by absolute power God can do things other than those he foresaw that he would do and preordained to do” (105; my emphasis). Ordered power — he foresaw that he would do — is God’s communication with the world and expresses, not limits, His absolute power.

16

The basic drive of anarchist politics is towards collective solidarity without the state: not exactly desiring self-management, therefore, but certainly desiring micro groups to organize and manage themselves without government regulation and monitoring. Anarchists distinguish themselves from libertarians by stressing, not the self, but the group, and separate themselves from the Catholic ideal of subsidiarity by denying in principle that the state can worthily assist those in genuine need or deal justly in matters of the common good. Agamben’s hope is that a final ridding of theology is also a final ridding of the provider state.

17

On this view, the West must return to what it was not long ago: a patchwork of self-determining enclaves and “principalities.” This is how the modern drive to the unified national provider state is eclipsed: with a fragmenting of the field of power, hence anarchist syndicates or municipal assemblies. We have met a similar idea before. Brunello Cucinelli’s business is consciously a revival of the Italian “age of communes:” an affirmation of the Italian social and physical landscape shaped in the Middle Ages by self-sufficient trading communes distant from the authority of the aggrandizing medieval papacy and Holy Roman Emperor.[11]

18

Scheler’s estate outlines the basic logic but equally important is the Thomistic axiom that grace perfects nature. We saw in Chapter 3 that subsidiarity requires government to defer to cottage industry. Cucinelli’s “School of Craftmanship” fosters the mechanical arts, which are about history and place. They express and reinforce the long life of the village of Solemeo: they build upon the physical memory of the thousands of villagers who built and rebuilt their homes there. These arts also assert the independence of the village, its competency to shape full lives for its young and old. They make a place “dense,” alerting others, and government, that deference is due to lands and lives organized around traditional skill and innovative work. To use Agamben’s terms, Kingdom must defer to the “age of communes.”

19

Kingdom and commune are organic, however, not oppositional: it is not to repeat Agamben’s equivocity. Schmitt helps here. He is an archetypal Tory and, for him, place is basic. He is, of course, interested in time and problems of concrete history but the core thesis of his The Nomos of the Earth (1950) is that an elemental gesture of human life is the manring. Humans form up their bodies collectively with the circle marking a boundary. This gesture is the ringing off of the sacred: in consequence, the city walls — as in Rome — take on a sacred character. A community and its laws take on an orientation from one place towards other places.[12] This entails apartness and prompts emblems of distinction: adornments and uniforms define manrings.[13] Veneration and the ornamental life are birthed together. Religion, no matter the faith, is incarnational. Embodiment always requires dressing.

20

One of Schmitt’s best interpreters, Heinrich Meier, stresses just how thorough a Christian mind Carl Schmitt possessed, but Meier means this to be cautionary: he thinks Schmitt espouses arbitrary divine positive law. I think Meier does not grasp well the peculiar burdens placed on Christian thought by the Incarnation. Christians celebrate the Incarnation as a great triumph, but they do not think it a simple triumph. As Jesus’ agony in the Garden of Gethsemane shows, nature does not easily yield even to the imprint of its maker’s will. Theology is fraught because the connection between the divine and the natural is tricky to specify precisely on account of the integrity of nature (AE, 229-31).

21

Not all is faith in Schmitt, as Meier supposes,[14] for straightforward entailments of the manring are veneration and borders. Schmitt is a bitter critic of what he thinks of as English civilisation: technology, industrialism, consumerism, and the entertainment offered by a commercial culture. These are negative for Tolkien too, but he would bitterly resist the claim these markers of civilisation are English — he seems obstinately to have refused to manage a motor car properly. Aquinas treated fascination with novelty as a leading indicator of vanity and Schmitt and Tolkien both think that the appetite for novelty — technological consumerism — severs us from any true regard for borders; it unmoors and makes one cosmopolitan. As Schmitt pithily puts it, Whig culture is all about the novum and indifferent to the ovum.[15]

Yet there are no borders without adornment, no communal identity without ornamentation and privilege. Liturgy and land, power and subsidiarity, government and distributive justice, faith and design, grace and nature are not opposed. No vestments without veneration. Agamben is right, they are linked, but he is wrong that the linking is a masking, a depoliticisation. Political theology can affirm vanity and the common good, as Aquinas argued. Oppositional fashion is possible, there are vestments imbued with power and vestments imbued with values that criticize power. Fashion is always theology, always privilege: Whig refinement can sustain Tory land and gods.

22

FOOTNOTES

[1] E. Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity (London: I. B. Tauris, 2013), pp. 179-207.

[2] See A. MacIntyre, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry (University of Notre Dame Press, 1992).

[3] H. Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem (Penguin, 2006).

[4] G. Agamben, The Kingdom and the Glory (Stanford University Press, 2011).

[5] C. Schmitt, Political Theology (Chicago, 2005), p. 46.

[6] G. Agamben, Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm (Stanford, 2015), passim; cf. C. Schmitt, Dictatorship (Polity, 2014), p. 83.

[7] Agamben is keen to stress the role of the Augustinian priest and seminal Early Modern philosopher, Malebranche, in Smith’s thinking (KG, 283-84).

[8] The Journey of the Mind to God, p. 11.

[9] For Pryzwara’s use of analogy, please see www.libertylawsite.org/book-review/all-valid-law-is-analogical/

[10] The Journey of the Mind to God, p. 34.

[11] www.brunellocucinelli.com/en/solomeo#the-territory.

[12] C. Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth, Biblio? pp. 74-5.

[13] See C. Schmitt, Theory of the Partisan (Telos, 2007). A word of caution. Aurel Kolnai examines the Nazi use of ideas like the manring. I discuss at length his treatment in an article forthcoming from the Hannah Arendt Institute for the Study of Totalitarianism, Dresden. Once it appears I will write a blog post about how this idea of the manring can be “safely” used.

[14] H. Meier, Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss (University of Chicago, 1995), pp. 77-78. For a little more elaboration of this point.

[15] C. Schmitt, Political Theology II (Polity, 2008), p. 128.