Fashion & Civilisation:

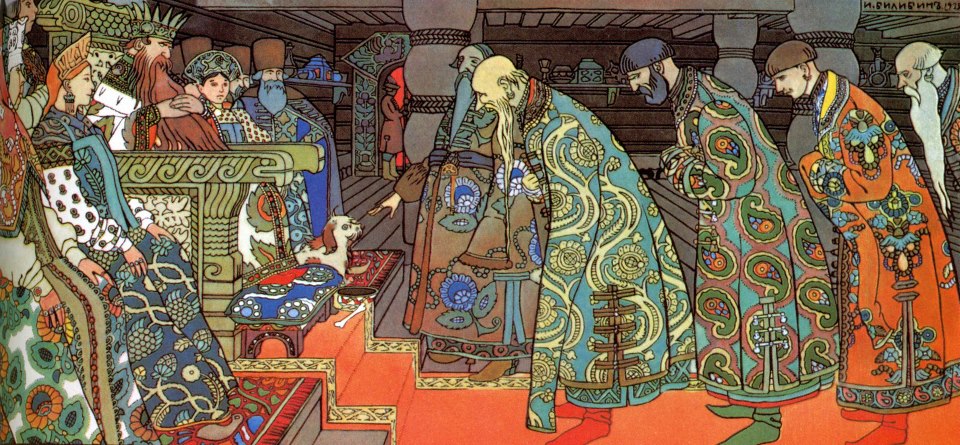

Johan Huizinga and Fantasy Fashion

Is fantasy opposed to truth and goodness? Is fantasy false? Is Scheler right that role-play is problematic? Smith’s ethics, he argues, is fatally weakened by reliance on role-play because it lacks true intimacy; it smuggles Cartesian isolation into ethics. Aquinas affirmed the place of rhetoric against Platonic exactitude but another challenge to Scheler comes from an unlikely source. The master of rectitude himself, Kant, argues that toys, games, and fantasy might not be the same as morality but insofar as they build civilisation they offer a robust surrogate of morality.[1] If masks, uniforms, wigs, and costumes, the garments of role-play, build civilisation, how right can Scheler’s criticism be?

Indeed, since Kant thinks the moral life is rare, the games of civilisation really are the quasi-moral glue of social order. Aware of play’s peculiar metaphysical and moral standing, Aquinas says:

Wherefore excessive play is that which goes beyond the rule of reason: and this happens in two ways. First, on account of the very species of the acts employed for the purpose of fun, and this kind of jesting, according to Tully (De Offic. i, 29), is stated to be “discourteous, insolent, scandalous, and obscene,” when to wit a man, for the purpose of jesting, employs indecent words or deeds, or such as are injurious to his neighbor, these being of themselves mortal sins. And thus it is evident that excessive play is a mortal sin. Secondly, there may be excess in play, through lack of due circumstances: for instance when people make use of fun at undue times or places, or out of keeping with the matter in hand, or persons (ST II-II, q. 168, a. 2).

2

Although Aquinas does not draw upon the creative power of play he sees it as of apiece with civilisation. It assumes order, known rules of courtesy, and justice. He also sees what is most essential: play has its time and place. This chapter proposes that fashion and style are part and parcel of civilisational order and their playful and fantastical elements are woven into rule of law. Think only of a judge’s wig or a knight sporting his beloved’s colours. These might seem frivolous but as the work of Johan Huizinga and Adam Ferguson demonstrates, games and civilisation go hand-in-hand. And sometimes a knight sporting his beloved’s colours is not remotely frivolous. In the Battle of Britain, British fighter pilots would attach their wives’ and girlfriend’s bras to their cockpits,[2] and as Churchill reminds us: never was so much owed by so many to so few. As I will show, James Bond’s style is no mere window dressing.

3

Since the end of World War II the West has been stable. Our lives have been predictable. Few disasters and no catastrophes have broken the regular unfolding of our days for 70 years. Written in 1947 Albert Camus’s The Plague imagines a modern unexceptional city succumbing to the bubonic plague. It is a riveting story and opens cinematically: a doctor leaves his apartment for work one morning and going down the stairs sees a rat lying on one of the steps dead. Puzzled, but not overly, he side steps the rat and goes about his day. The doctor’s everyday circumstances are about to change utterly.

4

Camus’s novel addresses the existential and political consequences of a collapse in normal circumstances: whole families rapidly fall to the plague, soldiers ring the city, organized crime turns to running the blockade, and burying the dead becomes perfunctory. Interestingly, Camus has the doctors becoming hated figures as their arrival at a home means families will split up, the sick moved to hospital to die alone and other family members put in quarantine.

5

Dramatizations of people trying to cope with the collapse of civilisation fill our screens. Films that come to mind are I Am Legend, the Brad Pitt vehicle World War Z, and amongst TV series, Lost, Battlestar Galactica, Fortitude, and The Walking Dead. Then there are the white walkers in Game of Thrones and Ned Stark’s warning, “winter is coming.” Nor is it a matter of our dramatizations alone. The November 13th Paris Killings prompted France to invoke emergency law. Going to a football match, eating out, and concert going ended in mass killings and radical police powers were judged necessary to maintain the everyday patterns of French life.

6

Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) is best known for his theory of politics in abnormal circumstances. Thought by many to be the most profound work of political theory in the twentieth century, his Concept of the Political gives the analytics of such a politics. Schmitt’s book dates to that dark year 1933 and thinkers like Aurel Kolnai (1900-1973) and Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) did not think that mere coincidence. In his brilliant Homo Ludens (1939), Huizinga picks out Schmitt’s claim that abnormal circumstances must be understood as a serious emergency (Ernstfall).[3] Huizinga turns this central claim upside down arguing that only the playful is adequate to abnormal situations for the ludic is the soil of civilisation.

7

It might seem strange to respond to the dire with playfulness but Huizinga ranges across fashion, art, poetry, philosophy, politics, war, and diplomacy, to demonstrate that the ludic makes civilisations resilient. In a remarkable history of play, Huizinga identifies what he calls the “magic circle of play” (Huizinga, 11) in religion, politics, and commerce.

8

At the Mass, the priest role-plays being Jesus at the Last Supper. Dressed-up in costume, the priest makes elegant ritual gestures: accompanied by song, these gestures happen in a space and a time set apart for the spectacle. The aesthetics of the event are not much different from a soccer match. Of a Saturday, hallowed fields, like Anfield, home of Liverpool Football Club, fill with thousands of supporters dressed up in colors; supporters who, for a defined period of time, ritualistically gesture and sing as they cheer on their costumed players. Games in which clothes are prominent solidify community identity.

9

The king had his court jester and seldom a day goes by when we don’t marvel at the clownishness of our politicians. A British Prime Minister wins the joust that is Prime Minister’s Question Time in Parliament if she can transform the Leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition into a Pantomime villain. Laughter and jeers greet every political put down. The entertainments of Parliament are not much removed from those of a tavern. And like tavern games, political gamesmanship draws the different sides of communities together.

10

Our comedy shows confirm that office life is a series of “contests, performances, exhibitions, challenges, preenings, struttings and showing-off, pretences and binding rules” (Huizinga, 47). An excellent summary of commerce as game is offered in the super speech delivered by Jeremy Irons in Margin Call, a 2011 film portraying the reckless financial gambling that gave us the turmoil of the 2008 financial freeze. Adam Smith does not disagree. He insists commerce only functions in light of exhibitions of wealth. Design objects and fashionable accessories are, as Adam Smith puts it, “toys of frivolous utility,” and yet they stir the fantasies of an entire civilisation. Toys generate communities.

11

Countries need role-play, costume, and fantasy, if civilisation is to forge bonds resilient in abnormal circumstances. Moral formalism, insists Huizinga (and Kant agrees), must be “rooted in the primaeval soil of play” (Huzinga, 5) and countries must affirm rather than run from their heritage in religion, politics, and commerce. Clothing and design is inseparable from this heritage. The priest has his vestments, the nun her habit. The politician has her power dressing and the carefully choreographed “look” for the factory visit or county fair. Business formal or causal is much the same and careful attention to the watch worn or handbag carried is part of “emotional intelligence.” Rule of law depends on dress-ups,[6] and so does war: the judge, police officer, lieutenant or squaddie, all don uniforms.

12

Legal and moral formalism needs geography: there is no play without a playing field and no playing field without a vigorous sense of place. Play “proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space” and games have a tendency to found clubs. Think only of our tennis, soccer, and golf clubs, to name a few and the dress codes that each requires. This being “apart together” is basic to play but it does not mean parochialism.

13

Teams combine into leagues, associations, and even governing international bodies.[7] Historically, many games have been cruel and bloody and Huizinga observes that war and diplomacy have the attributes of games. Sides are taken, people dress up, dummies and cheating attempted, and ferocity lights up the contest. However, like all games, there are limits: geography shapes borders and the field of battle, there are long-established rules of engagement, as well as expectations of honour, decency, proper form, and being a good loser. Gamesmanship is expected but so too is a sporting chance[8] and being a spoilsport brings opprobrium upon an adversary and even nations. Despite the contest the play forms are recognized internationally and all communities are required to observe them or live with the consequences.

14

These points crystalize around James Bond: the man with license to kill the enemies of the Queen. His is a serious commission: defeat criminal masterminds intent on subverting rule of law. Why then the drollery and one-liners? Are the playful elements of Bond mere entertainment, ancillary to the serious core of fighting subversion?

15

Amongst the seminal books generated by the Scottish Enlightenment is Adam Ferguson’s work of political anthropology, An Essay on the History of Civil Society (1767). Containing many gems, a highlight of the book is a demonstration that the fables and romances a civilisation uses to entertain can have dramatic impact on its mores. Ferguson (1723-1816) shows that the medieval literary ideal of the knight transformed both the practice and manners of war. The Middle Ages also gave us James Bond.

16

Before this ideal, Ferguson contends, war was typically a matter of ambush, revenge killings, and desire for spoils: nor was any distinction made between combatants and non-combatants, and defeat meant death or slavery. Medieval romances demanded gallantry from a knight and slowly but surely real expectations of soldiers changed. Refinement and courtesy of officers, indifference to spoils, a fair fight, leniency to those who surrender, and a rigorous isolation of women and children from reprisal, all became part of the just conduct of war. All of us can come up with examples when soldiers failed the ideal, but cynicism would falsify the historical record, also.

17

Ferguson identifies three cultural tributaries for the knight’s gallantry. From the Celts, the formalities of the duel and the idea of combat as juridical. The Germanic tribes twined war with a veneration of women, believing female gods, the Valkyries, would decide the outcome (cf. AE, 491). Christianity contributed obedience to the rule of humble service to neighbour. The result: “The hero of modern romance professes a contempt of stratagem, as well as of danger, and unites in the same person, characters and dispositions seemingly opposite; ferocity with gentleness, and the love of blood with sentiments of tenderness and pity.”[9]

18

Chaplain to the Scottish regiment of the Black Watch, Ferguson was a great admirer of the Celtic mores he observed in his soldiers. Duels and judicial combat ooze a sense of the ludic and perfectly capture Ferguson’s fellow countryman, James Bond.

19

Glib one-liners dripping off his tongue, the Swiss-Scottish Bond has “a contempt of stratagem.” As befits a Commander in the Royal Navy, Bond lives by Lord Nelson’s advice, “just go straight at ’em.” One for sauntering into the enemy’s lair, impeccably dressed, Bond likes to challenge others to a duel. This is explicit in The Man with the Golden Gun where Moore’s Bond and Scaramanga literally duel: playing a game of hide and seek amongst illusion generating mirrors, the game begins pistols drawn and twenty paces walked.

20

Play conveys rule of law. Lawyers rhetorically duel and joust, following rules of procedure, and should it come to it, meet at the court, where pleas (derived from the Anglo-French word plai) are submitted to a judge in costume, and oftentimes a wig, who umpires the gamesmanship. Little wonder then that Bond responds to those seeking to subvert rule of law with a vigorous assertion of play. What better way to deflate the spoilsport than to reassert the ludic roots of law?

21

A court of law is like a playing field, a space where rules and outcomes are decided. Contempt of court tells participants what is out of bounds, just as certainly as does the throw-in and goal kick. Bond has a number of choice playing fields. We first meet Bond in Dr. No, in Black Tie at the roulette table. Winning against a beautiful woman, Bond is all charm, as keen as any ancient German to keep the female gods on side. No hard feelings at money lost, she leaves the table with Bond who promptly asks: “Do you play any other games?”

22

As every Bond fan knows, Bond’s favourite game is, in fact, motor rallying. The racetracks might be the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul, or the streets of Rome, but speed racing, whether motor cars, motor bikes, power boats, and even parkour, is a Bond perennial. The cars involved — the British marks, Lotus, Jaguar, Aston Martin, and the delicious Sunbeam Alpine — are not accidental.

23

Court cases, like war, and games generally, are agonistic. Sides are taken, participants and spectators alike dress up in team colours, sport a sigil, or invoke ritual. New Zealand’s national rugby team, All Blacks, is famous for its Maori war dance before games. After Iceland’s 2016 Euro run, football fans the world over are now familiar with the intimidating Viking handclap ritual. Games can be bloody and damaging: boxing and fox hunting get bloody, and court cases can damage reputations forever. Bond’s famous gentlemanly style shows he is on the side of the forces of The Establishment. Cinematic shots of London’s government buildings with Bond in Savile Row tailoring are common and contrast with the underground lairs of the masterminds of the secret society, Spectre. One of the most iconic scenes has Bond skiing off a mountain cliff, surely doomed, only to have a Union Jack parachute open up. Bond flies the flag.

24

Bond is always sporting, and sporting design. His British sports car, the Aston Martin, is part of his team colours — movie goers literally cheered at the sight of his vintage DB6 when it reappeared in Skyfall — and it, too, is part of the game: the work of Q, the car performs dummies, foxing the enemy with trick features like ejector seats. Most famous of all though is the Lotus driven by Roger Moore’s Bond that saves Bond’s bacon by converting from sports car to submarine and back again!

25

Less theatrical than the foppish Bond of Sir Roger Moore, the brutalist Bond of Daniel Craig still offers a fair fight. Craig’s arrival in the role began famously with a “horror of war” scene: Bond and his adversary, both badly dressed and rumpled, confront each other in a raw physical struggle stripped of all glamour. The setting, irony laid on thick, is the Gents. Finally gaining an advantage, Bond pushes the man’s head into a toilet sink in a men’s lavatory to drown him. It’s a “fair fight,” it could have gone the other way, with Bond dead. He has no special toys from Q to eek out an advantage. Indeed, Bond almost dies: the man being drowned plays a dummy and fakes his death; Bond, tricked, turns his back only for his adversary to seek out a gun. Villain aiming at Bond’s back, the scene ends with Bond’s signature swivel shot. Even a blaggard gets a sporting chance: everyone gets to play the zealous advocate.

26

Despite the brawn and chip-on-the-shoulder aggression of the Craig Bond, the Connery incarnation is more sinister. The Scottish Connery takes to heart Ferguson’s “ferocity and gentleness.” The almost lullaby quality of Connery’s accented speech cannot really hide his chilly indifference when killing. Some have noted that Connery literally moves like a big cat, power elegantly on the move, but he also shares a cat’s cold amusement with its prey. From the first and most iconic of all the films, the well-known scene from Dr. No when Bond kills Professor Dent: pretending to not notice Dent going for a gun, and watching the professor’s excitement mount at possibly killing a British secret agent, Bond dispatches him very coldly.

27

But Dent, as the phrase goes, “had it coming to him.” Professor maybe, but also willing to have others unjustly gunned down. Bond is also the cold part of justice, no matter that his combat is redolent with the themes of fashion and play that in fact sustain rule of law. A creation of the West’s knightly tradition, the gentlemanly knight holding the abnormal at bay so that normal life continues, has universal appeal. Bond’s brand, a brand properly belonging to the Middle Ages, continues to build, and build internationally: think only of the monkish Jedi of Star Wars with flashing light sabres, Harry Potter with his cape and wand, Gandalf with hat and staff, Katniss Everdeen, whether in ball gown or dressed in leathers, bow and arrow in hand, or Jon Snow in winter cloak wielding an ancient steel blade, and the list goes on.

28

FOOTNOTES

[1] I. Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (Cambridge, 2009), pp. 42-44.

[2] E. Wilson, Adorned in Dreams, p. 56.

[3] J. Huizinga, Home Ludens (Beacon Press, 1950), pp. 208-09.

[4] A variant of this idea is basic to fetish and amply on display in the Sacher-Masoch classic, Venus in Furs (Zone Books, 1991).