Fashion & Poverty:

The Whig-Tory Debate

The individualism of our postmodern and globalized era favours a lifestyle which weakens the development and stability of personal relationships and distorts family bonds

-Pope Francis[1]

1

People would be astonished if Pope Francis ever made the fashion pages. Pope Benedict famously did when he wore red leather slip-on shoes. Made by the papal cobbler they nonetheless resembled some shoes made by Prada. It was a delicate moment for Prada. Pope Benedict is no David Beckham, happy to contract out his image. The shoes were not even Prada but the mix up was an advertising coup, if rightly managed.[2] The raffish red slip-ons have been banished by Francis, along with many other papal vanities.[3] That will not stop the fashion world coming to Francis for inspiration, all the same.[4] [5]

With his keen insight into human foibles, Aquinas would be highly amused by the red shoes fracas: Has the modern papacy hardened its position? As shown in the Introduction, the criticism of commercial civilization is not at all new with Francis: despite his red shoes, Benedict himself used stronger language. Have the patrons of Bernini mutated into Hume’s “severe moralists”?

2

In his contributions to [the_tooltip text=”CST” tooltip=”Catholic Social Teaching”], Francis is continuing a long standing papal meditation on the body and expressing the belief that our understanding of embodiment is warped.

What do people hope for? The world over it is the same: a home, with family fed, healthy, and competent, and friendship amongst the generations. Belonging: a place that requires work but also gives membership; a rich identity, those belonging dressed decoratively in the markers of that membership. And a relationship with the divine: globally, people participate in stylized rituals in honour of their gods, some in hope of continuity for the community, others in hope of personal continuity.

3

But is hope still relevant in today’s world?

For Pope Francis, the answer is emphatically “yes.” His 2015 Laudato Si’ was a bombshell, but the charge was primed in his 2013 Apostolic Exhortation, The Joy of the Gospel, which caused a stir with its talk of a “tyranny” of markets (EG, para. 56; [the_tooltip text=”LS” tooltip=”Laudato Si”], para. 117). Much quoted by the press were his words: “Today we have to say `thou shalt not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills” (EG, para. XX; [the_tooltip text=”LS” tooltip=”Laudato Si”], para. 95). The press could also have cited: “The worship of the ancient golden calf (cf. Ex 32:1-35) has returned in a new and ruthless guise in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose” (EG, para. 55;[the_tooltip text=”LS” tooltip=”Laudato Si”] , para. 118). Hope, for Francis, is a call to cleanse the economy: “an evil embedded in the structures of a society has a constant potential for disintegration and death. It is evil crystallized in unjust social structures, which cannot be the basis of hope for a better future” (EG, para. 59;[the_tooltip text=”LS” tooltip=”Laudato Si”], para. 108 & 6).

4

Some perceived an economic analysis released by J. P. Morgan at the time of the Apostolic Exhortation as a rebuke of the pope.[6] Unconcerned with the pope’s ideological coin, the J. P. Morgan document argues the pope is factually wrong: today’s economy is not one of exclusion, inequality, and murder.

5

And surely, the bankers have a point. Just how prevalent can poverty be when the WSJ is running a series of articles on “global gluttony” with titles like, “As World’s Kids Get Fatter, Doctors Turn to the Knife.”[7] Paul Collier, Director of the Centre for the Study of African Economies at Oxford University, and author of the highly regarded, The Bottom Billion, argues that all countries participating in the global econony benefit, the exceptions being those countries mired in war, perverse government, or landlocked with crippled infrasctructure (on account of the previous two reasons).[8] Amongst hundreds of examples, in the decade since Bangladesh attracted the manufactering business of the fast fashion houses GDP in that country has doubled.[9] In ten years! Although working conditions are hard in the garment factories – indeed, hardly bearable by Western standards – conditions are better than those in the argricultural sector, the fate of almost all in Bandladesh before the arrival of fast fashion manufacturing.[10]

6

In my opinion, the J. P. Morgan argument cuts deeply[11] largely because of the power it draws from the Scots. Hume’s formula seems to work every time.[12] In a 2014 article in the WSJ, Bill and Melinda Gates have this to say:

In our lifetimes, the global picture of poverty has been completely redrawn… Here’s our prediction: By 2035, there will be almost no poor countries left in the world. Yes, a few unhappy countries will be held back by war, political realities (such as North Korea) or geography (such as landlocked states in central Africa).[13]

7

Alive today, Hume would say to Pope Francis that he has already delivered on the hope of a world with little poverty (EG, para. 188). There is now no more room for hope. The problem it responds to is solved. [14] For Hume, the city means we are more beautiful in the aggregate than ever before,[15] healthier, more hygenic,[16] engaged in more complex work, better dressed, and more ornamental. Of course, some individual lives may still be psychologically fraught, but in the aggregate, Hume will insist, the problem posed by hope is solved. Now let us enjoy our cities and entertain one another!

8

Has fashion banished the biblical principalities of darkness (cf. Ephesians 6:12)? Francis thinks not:

But a sober look at our world shows that the degree of human intervention, often in the service of business interests and consumerism, is actually making our earth less rich and beautiful, ever more limited and grey, even as technological advances and consumer goods continue to abound limitlessly. We seem to think that we can substitute an irreplaceable and irretrievable beauty with something which we have created ourselves (LS, para. 34; cf. para. 46).

9

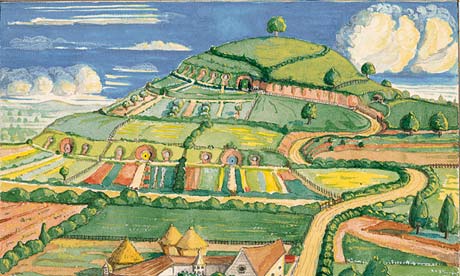

Is Pope Francis oddly out of touch? Confusions about the man abound. We’re told that Francis exhibits a “friendlier approach to secular culture.”[17] Since secular culture is commercial civilisation it is not clear his denunciations of this golden calf is a “friendlier approach.” I suggest Francis is a Tory. I have written about Tolkien as such.[18] In eighteenth century Britain the Tories lost to the Whigs on what would henceforth hold sway over the culture. The Tories defended the inheritance of the Middle Ages, where most people lived on the land, either as parts of estates owned by the Church and aristocracy, or as small farmers or yeomanry. Town and city life was marginal in orienting culture. The Whigs sought to reverse this emphasis and transform the country from being largely agricultural to primarily commercial, with culture basically oriented by city living.[19] Adam Smith was clear about one of the implications: under the Whig Settlement there would be a gradual dissolving of familial and territorial loyalties ([the_tooltip text=”TMS” tooltip=”Theory of Moral Sentiments (Adam Smith)“], 222-23). Mobility, speed, and change became a central motif, not stability. Over a century after the Whigs vanquished the Tories, Tolkien, along with others, expressed dismay at what the Whigs had wrought. Tolkien was a conservative Catholic gentleman committed to the Tory sensibility.[20] Francis is of the same mold ([the_tooltip text=”LS” tooltip=”Laudato Si”], para. 44-46; 67, 70, 84, 98, and especially 94).

10

About Hume’s fashionable cities, Francis says:

New cultures are constantly being born in these vast new expanses where Christians are no longer the customary interpreters or generators of meaning. Instead, they themselves take from these cultures new languages, symbols, messages and paradigms which propose new approaches to life, approaches often in contrast with the Gospel of Jesus. A completely new culture has come to life and continues to grow in the cities (EG, para. 73).

11

What is the psychology birthed with this “completely new culture” of the city? What are the consequences of “rapidification” (LS, para. 18)? In a moment, we shall turn to the clues developmental psychology can give us.

12

The media frenzy around the publication of the exhortation and encyclical ignored the hundreds of footnotes in the documents. In the media’s telling, Francis is a breath of fresh air. Benedict’s profound love of cats and fluffy kittens did nothing to dent the media’s caricature of him as a “grim-faced German theology scold.” If journalists could be bothered to be serious-minded for a moment they might be astonished to read all the citations to works by Benedict in Francis’s writings and surely it is no part of the media script for the popular Francis to be looking back to the chastizing figure of John Paul II?

13

All remember Saint John Paul II as a culture warrior: a pope seldom not talking about abortion and euthansia as profound corruptions of civilization, engines of, in his famous phrase, the culture of death. His 1995 encyclical, Evangelium Vitae, also spoke of tyranny, about those states in the West that have legalized the systematic killing of the weak by the strong. The encyclical argues that the strong have clubbed together in a conspiracy against the marginal (LS, para. 34, 104-05, 107): with respect to the weak, unprotected, and disabled, state law in Western countries retorts with Cain “Am I my brother’s keeper?”[21] Francis can say our “economy kills” because the popes have long held that at the heart of modern commercial life is killing.[22]

14

The last three popes, therefore, have a common teaching: isolation from others, lack of solidarity, creates a destructive and oftentimes murderous poverty.

15

One of the deepest forms of poverty a person can experience is isolation. If we look closely at other kinds of poverty, including material forms, we see that they are born from isolation, from not being loved or from difficulties in being able to love… man is alienated when he is alone…

16

What is the exact character of this poverty? Perhaps we can accurately state the argument of Pope Francis this way: the contemporary econony creates wide-spread vulnerabilities (LS, para. 149); it puts in jeopardy psychological development by fracturing families and isolating many by their very labour; it unhinges us from the myriad civic relationships that foster human development (LS, para. 43-46).[23] In moral theology, hope is a species of courage, a response to fear. Hope aims to transform our fear, to change anxiety into freedom, so that throughout the life span we make positive adjustments in matters of sexuality, child-bearing, parenthood, career, civic, and religious participation, and when dying, too. The contemporary economy mangles the conditions required for these psychological adjustments: hope demands an overhauling of the economy, therefore.

17

Why, despite the undeniable gains since Hume, is isolation endemic?[24] Hume himself gives the hint: in commercial life, people flock to the cities[25] to show off; so that others see their wit and breeding, their taste in furniture and clothes. The darkness to which hope responds (LS, para. 59, 79) is at the heart of the Humean city, its very engine: vanity.

18

In De malo, Thomas Aquinas identifies the deep structure of vanity as the desire to make manifest one’s superiority over others (LS, para. 90) or, at the very least, never to be seen as inferior.[26] Thomas argues that vanity has a double structure: it boasts so as to vaunt the self over others and simultaneously works to diminish other people in the eyes of their neighbours. Interestingly, Immanuel Kant calls this phenomenon “fashion”![27]

19

Why is vanity a deadly sin? Think only of the great opening shower scene in the film, American Psycho. Francis writes: “The culture of prosperity deadens us; we are thrilled if the market offers us something new to purchase” (EG, para. 54). Patrick Bateman is meant to be you and me. Each of us is, the film contends, because submerged in America’s commercial life, compulsively vain and murderous. Vanity existed long before commercial societies but the glamour of commercial life, the luxury made possible by it, intensifies the spell of vanity. As Francis observes, our technologies encourage a rush to isolation (EG, para. 87-90). We vaunt ourselves above others but also trigger an abandonment of our own selves in seeking so desperately the approval of others. A perverse double isolation, from others and self, is the consequence. Francis quotes Cardinal Newman on civilizations turning into deserts (EG, para. 86; cf. para. 93): deserts where the indifference of Cain prevails (EG, para. 211).[28]

20

Francis’s opening sentences speak of a desolation wrought by consumerism (see also para. 196). Not all agree: well-known psychologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett welcomes globalization: it allows the young to make their own choices about love, work, and personal values, as traditional ways of life wither:[29] a point predicted by Adam Smith in 1759. Arnett documents the negative reaction of elders in China and Japan to the youth becoming increasingly individualistic.[30] Japan even has a harsh label for such, `parasite singles.’[31] Francis speaks of “today’s self-centered culture of instant gratification” (LS, para. 162). The allurements of the best jobs make the young postpone adult roles:[32] in every industrialized society, Arnett observes, young adults transition into adult roles in their mid to late twenties: for example, in America today the average age for marriage is 28 and for parenthood 26; in 1970 the average age for a first time mother was 21.[33]

21

In the wake of individualism, you find relativism, loss of rule of law, and government corruption (LS, para. 122-23). Standing apart from the common good, individualism is the belief “we enjoy absolute power over our own bodies,” which “turns, often subtly, into thinking that we enjoy absolute power over creation” (LS, para. 155). Unsurprisingly, a study conducted in five countries – the U.S., Nigeria, Peru, Pakistan, and Mexico — shows that in three out of the five – the U. S., Peru, and Mexico — women give continuing with school, the demands of work, and the rigours of the daily schedule, as the main reasons for having an abortion.[34] And the study found that in all countries economic reasons prompted abortions[35] and subsequent internalized dissonance with keenly held beliefs.[36]

22

The dissonance is predictable, thinks Francis, for we are “linked by unseen bonds” (LS, para. 89) with a need to feel “at home” (LS, para. 151) but solidarity is the only antidote to “being adrift” (LS, para. 65; EG, para. 91). Absent solidarity darker motivations[37] prevail and society becomes “a mass of individuals placed side by side, but without any mutual bonds” (EV, para. 20).[38] The delay and rupture of family life for the sake of career leaves some individuals overwhelmed, lonely, and dissatisfied, psychologists observe.[39] Childlessness is increasing throughout all strata of American society and the childless report loneliness on account of their friends breaking off when they have children.[40] The loss of prestige for fixed married family life can result in isolation too dark to be commonly discussed: evolutionary psychology believes it has a handy explanation for why children are more at risk of being killed by their step-fathers than by their natural fathers.[41] The Atlantic Monthly reports body-image and isolation stalks certain children: “Non-poor children living with married step-parents had a 67 percent higher risk of obesity compared to similar non-poor children raised by married biological parents.”[42]

23

Echoing these isolations in that part of the life span concerned with fertility, sexuality, marriage and family,[43] is loneliness at the end of life. Francis speaks of “the abandonment of the elderly and infirm” in the city (EG, para. 75). A study by Balber found that the loneliness of the dying and disabled stems from the contrast of their immobility and slowness with the pace of modern life, its productive and competitive ethos.[44] Francis comments: “In the prevailing culture, priority is given to the outward, the immediate, the visible, the quick, the superficial and the provisional” (EG, para. 62). A study by Block and Billings concludes that many requesting an end to life are actually looking for aid and company in living out the rest of their lives.[45] This is complicated by the fact that a commonly expressed want of those in palliative care is mending broken relationships and reconciling with estranged family.[46] Psychological studies show that a majority of patients would like to spend their last days at home instead of in a hospital setting[47] and also show that caregivers of loved ones who die connected to ventilators in a high tech setting are three times more likely to suffer major depression six months after the passing.[48] This is a chilling phenomenology of technoscience (LS, para. 102-03).

24

A New Zealand study looks at reasons why some healthy seniors support euthanasia. Much has to do with their experience of what they witnessed when family members were previously sick and how they fared in clinics. Many expressed disgust at the use of medical treatments they had seen and the resulting quality of life of their loved ones. Expressing their fears, suffering, of course, ranked prominently, but so too did a perception of loneliness and being a burden.[49] Palliative research shows that the experience of pain diminishes when the elderly believe they are the object of care and concern.[50] However, the tempo of dying contrasts markedly (LS, para. 114) with the obsessions of the ordinary world[51] and one can only imagine these psychological experiences exacerbated if public policy discussions openly consider killing the sick for the sake of the nations’ financial health, and such conversations are already happening.[52]

25

The problem of contemporary isolation supports Pope Francis’s polemic against Hume. Certainly, we are healthier, wealthier, cleaner, and prettier than when Hume first found us, but significant dislocations brought about by the pursuit of luxury have not merely generated unhappiness but fostered killings of the weak. Some argue that the sum total of homicides have decreased these last two hundred years – see the notable work by Pinkers – but the killing of the defenceless is in full flow, each year around 43 million globally.[53] Vanity exludes and vanity is deadly. This is an unbroken teaching of the Church from Gregory the Great through Aquinas to Pope Francis. Vanity and its social form, the city, have pushed multiple moments along the life span, and the slowness of disability and sickness, into harrowing conditions (LS, para. 117).

In this chapter, I have presented the Tory indictment of our age of fashion. Mindful of it, the remainder of the book is an effort to show that the fashion industry does contribute to solidarity and offers business models that span the Whig-Tory divide. In Chapter Five I will document that some of Francis’s concrete proposals are already structuring vibrant fashion houses.

26

FOOTNOTES

[1] Francis, Evangelii Gaudium: Apostolic Exhortation on the Proclamation of the Gospel in Today’s World (24 November 2013), para. 67; hereafter = EG. Cf. Francis, Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home (2015), para. 162; hereafter LS.

[2] “Does the Pope Wear Prada?” (Stacy Meichtry).

[3] “Benedict XVI, the best dressed pope” (Charlotte Allen: LA Times, February 17, 2013).

[4] http://tomandlorenzo.com/2015/07/tilda-swinton-at-the-valentino-couture-fashion-show

[5] http://www.buzzfeed.com/ellievhall/pope-francis-meets-adorable-baby-pope#.wnGgLZgBg

[6] See the blog of James Pethokoukis at the American Enterprise Institute, “A JP Morgan economist (in effect) responds to Pope Francis,” December 2nd, 2013.

[7] S. Wang, “As World’s Kids Get Fatter, Doctors Turn to the Knife,” WSJ (February 15th, 2014).

[8] Cf. D. Henninger, “The Growth Revolutions Erupt,” WSJ (February 27th, 2014).

[9] J. Bussey, “In Bangladesh, the Slow, Tragic March to a Better Life,” WSJ (May 30th, 2013)

[10] The Church cannot brush off the J. P. Morgan document for Francis has raised the stakes, declaring: “Our preferential option for the poor must mainly translate into a privileged and preferential religious care. No one must say that they cannot be close to the poor because their own lifestyle demands more attention to other areas” (EG, para. 200-201).

[11] A short case study is Mary O’Grady’s, “The Pope, the State and Venezuela,” WSJ (December 2, 2013).

[12] Hume could even point to Scripture and say he had fulfilled the universal call to work found at 2 Thessalonians 3: 7-12.

[13] Bill & Melinda Gates, “Three Myths About the World’s Poor” WSJ (January 18, 2014).

[14] S. Fidler, “Two-Track Future Imperils Global Growth,” WSJ (January 22, 2014).

[15] B. Leach, “Women are getting more beautiful, says scientists,” Daily Telegraph (July 26th, 2009).

[16] Absent from today’s world surely, but a regular occurrence in eigtheenth century England: judges provided with nose clips to ward off the stench of prisoners brought before the bar: see James Laver, The Age of Illusion (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1972).

[17] “The New Rome” by Francis X. Rocca (WSJ, April 4/5, 2015).

[18] Please see my, Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings: A Philosophy of War (Amazon, 2014)

[19] For an authoritative assessment of the meaning of Whig and Tory, see Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, Whigs and Whiggism (London: John Murray, 1913).

[20] A good example of this is Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, the television version being a huge cultural hit in the 1980’s.

[21] See the whole encyclical, but noteworthy are paragraphs 19-22. Cf. Max Scheler, Nature of Sympathy (London: Transaction, 2008), pp. 107-08.

[22] Francis writes: “Today everything comes under the laws of competition and the survival of the fittest, where the powerful feed upon the powerless” (EG, para. 53 & 54). For a similar thesis from a left anarchist position, see Giorgio Agamben’s Homo Sacer, and many of his other works.

[23] Cf. EG, para. 62 & 66-67. For a charitable but poignant account of modern work, de Botton’s work On the Pleasures and Sorrows of Work.

[24] Cf. EG, para. 75. See the data in Ari Fleischer’s WSJ article, “How to Fight Income Inequality: Get Married” (January 12th, 2014).

[25] Read the disturbing article, A. Browne, “China’s Left-Behind Kids Bear Grown-Up Burdens,” WSJ (January 17th, 2014). For evidence of the on-going urbanisation of America, see “Smallville, USA, Fades Further” (Neil Shah), WSJ, March 27, 2014.

[26] Thomas Aquinas, De malo (Oxford: OUP, 2003), p. 349.

[27] I. Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1978), p. 148.

[28] Francis speaks of a “globalization of indifference” (EG, para. 54) and an interesting example of this are a super-rich who live internationally roving between various cocooned homes: see “Stateless abd super-rich” (FT: Tanya Powley and Lucy Warwick-Ching, Saturday April 28th, 2012).

[29] J. Arnett, “The Psychology of Globalization,” American Psychologist, 2002: 57 (10), pp. 780-82.

[30] J. Arnett, “The Psychology of Globalization,” p. 776.

[31] J. Arnett, “The Psychology of Globalization,” p. 777.

[32] J. M. Twenge et al., “Generational Differences in Young Adults’s Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966-2009,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2012: 102 (5), pp. 1045-1062.

[33] D. Cohn et al., “Barely Half of U.S. Adults Are Married – A Record Low: New Marriages Down 5% from 2009 to 2010,” Pew Research, December 14th, 2011. On account of these delays, more American women are seeking medical help in getting pregnant: see Neil Shah, “More Women Try to Get Pregnant with Medical Help” (WSJ, January 24, 2014).

[34] A. Tsui et al., “Managing unplanned pregnancies in five countries: Perspectives on contraception and abortion decisions,” Global Public Health, 6, (2011), p. S 22.

[35] Cf. A. Adamczyk, “Understanding the Effects of Personal and School Religiosity on the Decision to Abort a Premarital Pregnancy,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, June 2009, p. 187.

[36] A. Tsui et al., “Managing unplanned pregnancies in five countries: Perspectives on contraception and abortion decisions,” p. S 2.

[37] Furthermore, a Swedish study looking into the power relations surrounding abortion, argues that teenagers certainly don’t experience having an abortion as their own choice but find themselves pushed around by partners, parents, medical staff, and school: Ekstrang et al., “An Illusion of Power: Qualitative Perspectives on Abortion Decision-Making Among Teenage Women in Sweden,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health (2009), Vol. 41 (3), pp. 176-78. Francis is not surprised (LS, para. 108).

[38] In what is supposed to be a celebratory piece in favour of abortion, motifs of dislocation and isolation come across prominently: L. Prine, “In Sickness and Health: Choosing,” Families, Systems, and Health (2002), Vol. 20: 4.

[39] P. Colman, “Abortion and mental health: Quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995-2009,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2011, p. 183

[40] L. Sandler, “The childfree life: When having it all means not having children,” p. 47.

[41] D. Buss & J. Duntley, “Homicide: An Evolutionary Psychological Perspective and Implications for Public Policy,” in Evolutionary Psychology and Violence, ed. R. Bloom & N. Dess (Praeger, 2003).

[42] Olga Khazan, “Can Your Family Make You Obese? New Research Reveals Parents’ Impact on Childhood Weight, Even in Rich Families,” The Atlantic Monthly, Feb 12, 2014.

[43] A Finnish study shows a doubling of the risk of suicide and an increased risk of exposure to violent death. M. Gissler et al. “Injury Deaths, Suicides and Homicides Associated with Pregnancy, Finland 1987–2000,” European Journal of Public Health (2005) Vol. 15 (5), pp. 459-463.

[44] P. Balber, “Stories of the Living Dying: The Hermes Listener,” in I. Corless et al., Dying, Death, and Bereavement: A Challenge for Living (New York: Springer, 2006), p. 119.

[45] R. Winograd, “The balance between providing support, prolonging suffering, and promoting death: Ethical issues surrounding psychological treatment of a terminally ill client,” Ethics & Behavior, 2012, pp. 44-59.

[46] H. Wijk & A. Grimby, “Needs of Elderly Patients in Palliative Care,” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, (2008) Vol. 29, pp. 106-111.

- 109.

[47] H. Wijk & A. Grimby, “Needs of Elderly Patients in Palliative Care,” p. 109.

[48] A. Gawande, “Letting go: What should medicine do when it can’t save your life?” The New Yorker (August, 2010).

[49] P. Malpas et al.,”I wouldn’t want to become a nuisance under any circumstances”—a qualitative study of the reasons healthy older individuals support medical practices that hasten death.” The New Zealand Medical Journal (2012): 9-19; cf. Billings, p. 557

[50] E. Cassem, S. J. “Narratives in Palliative Care” (2003).

[51] L. Scapira, “Passing Those Endless Hours,” Supportive Oncology, Vol. 8: 3 (2010), pp. 137-38. Reflecting on our everyday obsessions, Catholic theorists will need to concentrate afresh on the place of beauty in our lives and in theology. A good platform for thinking about this issue with Aquinas is Brendan Sammon’s The God Who Is Beauty (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2013).

[52] E. Dourado, “Why America’s Fiscal Reality Will Make Euthanasia Inevitable” The Umlaut (January 20th, 2013) and E. Emanuel & M. Battin, “What are the potential cost savings from legalizing physician-assisted suicide?” New England Journal of Medicine 339: 3 (1998), pp. 167-172.

[53] A. Tsui, p. 2. See Pinkers FAQ webpage where he straightforwardly denies abortion is a case of violence. Of course, he has to: not only because his social set demands it, but because it causes havoc with his overall thesis.