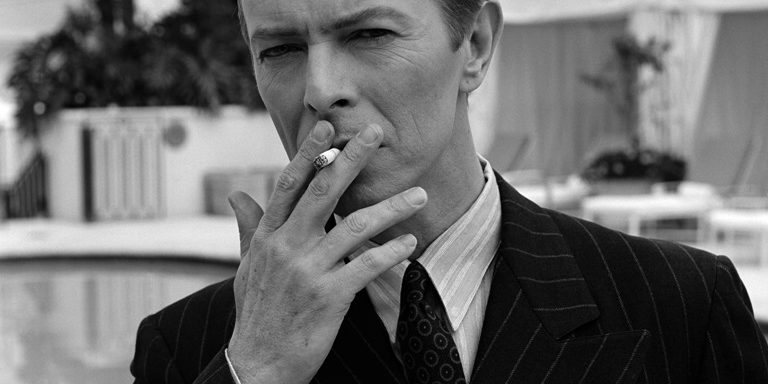

Here’s a new piece by my good friend Chris Wojtulewicz. It’s a fascinating inquiry into the tastes and meaning of rock icon, David Bowie. V&R is delighted to host another guest blog by Chris.

~~~~~~~~~~~

David Bowie’s Creed

Fragrance, Change, God

David Bowie used to like wearing Silver Mountain Water by Creed, as you will see in this interview with Olivier Creed back in 2013. This Alpine fragrance is not cheap, perhaps as you would expect. But if you ever smell this fragrance, it will carry with it the sense of what I have just said and what I am going to say. In other words, if you ever smell it, the thought will occur to you that this is only a short step away from standing in his presence.

If you know this fragrance already, you will add to it whatever you know and feel about Bowie. But is that all that would happen? Is it unilateral in this sense, now that you know it was the smell of choice for one of the twentieth century’s most successful musicians? Without having the Creed in front of you right now it will be harder to appreciate this; but is it not also the case that the fragrance could change your perception of Bowie? That even his music could, if you like, smell differently? Chalmers notes something very similar with listening to different kinds of music whilst driving.

I am sketching a back and forth relationship: the fragrance changes the perception of the object (with which it is associated); the object changes the perception of the fragrance. Anyone familiar with V&R will know the name of Erich Przywara, and recognise this ‘back and forth’ as part of the doctrine of analogy. It is the way that Przywara describes intra-creaturely metaphysics. In this case, the essence is not only present ‘in’ the fragrance (hence its ability to evoke something new when coupled with David Bowie), but also ‘beyond’ it—met only in the other object. And, naturally, vice versa: Bowie becomes both ‘in’ and ‘beyond’ the fragrance. Moreover, the meeting itself, precisely as movement, is an expression of the analogical relationship between the essence (essentia) sought and the movement towards it (existentia). This intra-creaturely metaphysical analogy is the basis of another, more fundamental analogy between the Creator and the creature. Perhaps more can be said, therefore, of the medieval analogical shape of Bowie’s life and career more broadly. We will return to this thought.

This might all sound a bit of a stretch. Metaphysical mechanics can suggest a kind of irrelevance—what Przywara, in fact, might call a ‘mathematical-grammatical interpretation’. But our guide to the analogical doctrine does not leave us wanting. To get how all of this is relevant and resonant one needs, as Przywara puts it, ‘a musical soul—that is, one able to feel the entirety of the content matter as vibrations, in order to understand them’ (RdG, p. 51).

In the aforementioned interview, Olivier Creed tells us that ‘a fragrance can always evolve, if only subtly. It’s like the painting that is never finished’. We might even call this the epectasy of fragrance. The impermanence, as Creed so clearly recognises, resonates with the changeable nature of Bowie’s career. Yet, this is not straightforwardly change. The sense in fact is that there is some essentia already within the fragrance’s possession, and yet towards which the evolution of the fragrance tends. The paradigm is as old as the pre-Socratics. Similarly with any of Bowie’s songs—or his career as a whole—its entire existentia is one of continuous movement; yet within and beyond it is to be found a rather surprising essentia.

Bowie spent his life continually changing and renewing his image and sound, defying all the odds by winning over a loyal fan base. He often spoke about writing from a place of alienation and isolation, which, combined with the ambiguous, hedonic-individualistic image from Ziggy Stardust on, might look a lot like nihilism or postmodernism.

Yet Bowie also admitted that he had always been driven by a ‘search for spiritual foundations’ and was interested in the concept of a ‘God beyond God’. This, I suggest, is the surprising essentia of his work. A more subtle understanding of Bowie’s art is to see it not just as a search for change and stability, of alienation and foundations; but the seeking of the one in and through the other.

‘No similarity between Creator and creature, however great, can be observed’—the Fourth Lateran Council declared in 1215—’without observing an even greater dissimilarity between them’. Like Bowie, the medieval Divines wanted to find a home for the eternal unchanging God in the movement and drama of human life. Analogy helped them traverse the gap; and Bowie’s career, taken as a whole, has the shape and form of this analogy more than any postmodern fragmentation. The inner trajectory of the change manifest was, counter-intuitively to many perhaps, a search for roots:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/-yY6t4ncfAM?start=90&end=124

Other-worldliness spanned not only the image of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, but through to his later works like ‘Dancing out in space’ (2013) and ‘Where are we now?’ (2013). Many dystopian themes are at play, from the distaste for revolutionary placards in ‘Cygnet Committee’ (1969), to the shunning of transient affection in ‘Modern love’ (1983). ‘Love is Lost’ (2013) expresses the instability of an uprooted life. Yet a catena aurea runs through it all: not a fetishising of change, but a reaching out to the stability which undergirds it. In this sense, Bowie’s work is less accurately described as change, than as a kind of ‘pushing beyond’ frustrated platitudes.

This does not lead to chaos. If anything, Bowie’s personal life crystalises into anonymous domestic bliss. The ‘analogical’ takes its medieval form in philosophical discussions of a God who is ultimately beyond language and knowability, and yet somehow foundationally present to the world. As the Fourth Lateran Council would have it, the dissimilarity, distance, transcendence of God is found in the moments of greatest similarity. Even more, the ‘alienated’, crucified God is the site of the most intimate, proximate, foundational presence of God.

The point is that, unlike in postmodernity, Bowie’s career does not ultimately point to the fetishising of alienation, but to a sort of ineffable stability beyond it. Everything is strange: the look, the voice, the contour of sound. But the music itself is not alienated: it is all very tied to the person of Bowie. This is why it is hard to imagine any of his songs adequately covered. Explored by other means, perhaps (think of Philip Glass’ symphonies, or the BBC Prom 19 in 2016). This tie to Bowie personally makes it almost cease to be music at all; but what is not to be missed here is the ultimate trajectory.

Being rock royalty should not result in increasing crystalisation of life, the laying down of roots, increasingly conventional appearance—yet this is all the way of Bowie. It only serves to emphasise that amidst the imagistic nature of the earlier manifestations, the analogous rationale is at work. ‘I don’t think I ever had a rebellion’, he told an otherwise shocked Michael Parkinson in 2002. On the contrary: ‘I wanted to get a lot of the world—I wanted as much as I could get’. A thirst for life was his catena aurea. In this way, Bowie makes postmodernism look practically conventional and predictable. He might not have concluded his search; but like the medievals before him, in the final analysis he frustrates the postmodern trope.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/yn18PohBzUY?start=2813&end=2919

There is something noble in the clarity of this admission. There is a certain vestige of the alienation theme, about which he so often spoke, in the Gnostic reference. His point about the frustration of the symbolic, with respect to God, is actually quite profound if taken the right way; but sadly becomes a bit lost in a theopanistic-panentheism whereby the ‘God beyond God’ pervades the cosmos (panentheism) or else is even fundamental reality itself (theopanism).

In short, this is reaching out to but falling short of the analogical. Bowie is, after all, a ‘musical soul’, and I would suggest experientially familiar with the illative sense. He seems to have sensed the mysterion of God: that God is ultimately beyond conceptualisation, as was (more accurately) expressed in the Pseudo-Dionysian tradition and by almost every Christian mystic ever since. Even the admission that there is ‘some merit in the chaos we perceive as our existence’ evokes analogy if by ‘chaos’ one means the rhythmic vicissitudes of oscillation between essence and existence. I just wish Bowie could have read Przywara.

RdG = Erich Przywara, Ringen der Gegenwart, vol. 1 (Augsburg: Benno Filser Verlag, 1929).