Our Baltimore garage poster is, of course, a cheeky poster. Professor Kass lays great stress on the Ten Commandments as the foundation of a community. Does the poster mean that the Second Amendment protects this community established by the commandments? And, if so, is it arguing that the Second Amendment is a crucial clarification of the meaning and scope of the commandments: that the sixth commandment – thou shalt not kill – is no straightforward restraint on human aggression or resentment, and nor could it be if the community formed by the commandments is to endure?

Does our Second Amendment poster even really argue that there is something implausible about the Ten Commandments, that they aren’t all that, in fact?

It is interesting that our poster tracks an internal division in the commandments which Professor Kass himself makes. Listing “do not kill” as the first commandment of the “second table” – the commandments respecting love of neighbour – Professor Kass does seem to acknowledge that the second table is natural law, that is, eternal and absolute moral principles. The Second Amendment clearly speaks to the Sixth Commandment and thus tracks this switch to natural law.

Is there any such switch though? Aquinas thinks not.

Aquinas argues that all the Decalogue is natural law. St. John Paul II speaks of two tables but argues they are ultimately one: “acknowledging the Lord as God is the very core, the heart of the Law, from which the particular precepts flow and towards which they are ordered” (VS, 11). And so Aquinas argues that keeping the Sabbath is “in conformity to right reason” (de Vitoria, 189) since in seeking God – a basic rational inclination, thinks Aquinas (see my post http://www.ethicsoffashion.com/corsets-natural-law/) – time must be set aside to be mindful of God (ST I-II, q. 100, a. 3, ad 2).

If there is no difference in ontological standing between the two tables there are some noetic differences. But even here an interesting difference emerges between Aquinas and Kass. The force of some precepts natural reason “of its own accord and at once” recognizes: these include, “do not kill,” “do not steal” and “honour thy father and mother.” Others require instruction by the wise, and others, such as the prohibition against idols, instruction by God (ST I-II, q.100, a.1).

Aquinas puts honouring mother and father alongside the precepts of the second table as precepts evident to unaided reason (Cf. de Vitoria, p. 171). One reason is because he thinks that being kind to benefactors is evident to natural reason (ST I-II, q. 11, a. 5, ad 4). Professor Kass disputes this and offers the compelling observation that our civilization shaped by the Bible takes honoring mother and father for granted, but thinks this is surely not the natural way of the world. He notes that the natural family is oftentimes a nursery of rivalry and iniquity, including incest and patricide, and cultures often honour heroes and leaders more than parents.

This is a rich dispute between Aquinas and Kass but we might note, for example, that Dante follows Aquinas, arguing that a particularly bad spot is reserved in hell for those who betray benefactors.

Professor Kass highlights the Decalogue’s great opening, the stark contrast between being with the Lord or being in “the house of bondage” (v. 2). This recalls the claim of Max Scheler (V&R Chapter 5) that you must either worship God or some other god, and the latter is bound to be much less nice.

Following from this, Professor Kass makes a striking point. Exodus 20, verse 3 reads: “Thou shalt not have other [“strange”; aherim] gods before Me.” Professor Kass renders this prohibition not as a declaration of philosophical monotheism but of cultural monotheism. He thus lays stress on the idea of strange gods.

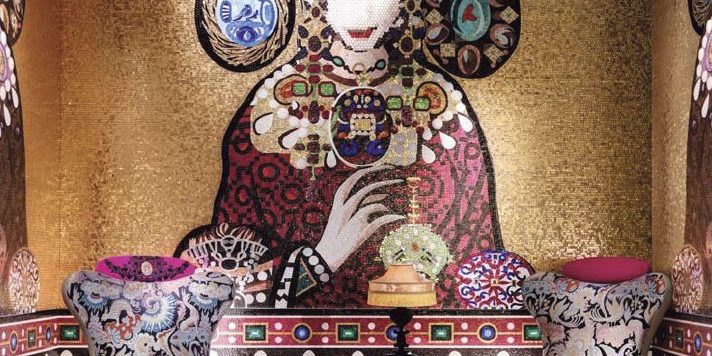

I love this point and I want to make it the content of my final and main remark. It is a claim about cultural monotheism because strange gods (v. 3) are linked to a prohibition of idols (v. 4) and thus foregrounds the connection between religion and artifacts.

The essential difference, thinks Kass, between the Lord and strange gods is that no god but the Lord can furnish the world with grace, kindness, and blessing.

I now come to a crucial point, one that links back to the de Vitoria quote above about graciousness.

Professor Kass translates the Hebrew hesed as grace but unlike the Latin gratia the Hebrew does not seem to have any link to poise. Now, I am no Hebrew scholar, but looking online I did not see a connection, as there is in Latin, to aesthetics. Grace has a bond with poise, and what is becoming and comely, because gratia has its root in gratus, meaning pleasing. Interestingly, the Greek and Latin translations of the Hebrew Bible translate hesed as mercy (eleos and misericordia, respectively).

The Hebrew hesed seemingly gives the religious a moral rather than aesthetic tone [aside: in the Q&A after the talk, Professor Kass agreed with this]. Kass argues that in the Commandments what is made holy is not a special object, place, or practice, but the time of your life. Something abstract, we might say, rather than bodily. This is repeated in devotion. About the Sabbath in the Decalogue, Professor Kass notes that no rituals or sacrifices are specified and that what is requisite is an absence, a cessation, a desisting. Of course, rituals and sacrifices will later be specified but for the Decalogue what is most basic is to affirm that the Sabbath is a call to remember that what has often been widely worshipped – heaven, earth, sea, and all they contain – is not divine.

This goes to the matter of embodied veneration or the problem of idolatry.

It is crucial to remember that this is a matter of stress or emphasis for as Professor Kass points out, earlier in Genesis the majesty and goodness of creation is affirmed. Still, the stress is there and thus we read at the end of Chapter 20 in v. 23 the prohibition against idols is reaffirmed: permission to have an altar of earth and a prohibition against, not a stone altar, but one of “hewn stone:” “for if thou lift up thy tool upon it, thou hast polluted it” (v. 25).

Kass gives five arguments against representing God in images. These are: worshipping things demeans persons; natural things are not salvific; crafting images of the divine is presumption for the principle of selection assumes a false intimacy; sophisticated idols can seduce us into venerating their makers; and finally, idols inherently celebrate human artfulness and thus necessarily obscure the reality of pervasive human twistedness (pp. 8-9). In his treatment of idolatry, Aquinas picks up on this darkness, noting that idolatry frequently involves the evils of mutilation and homicide (ST II-II, q. 94, a. 4, ad. 1).

I think each of these points excellent but Aquinas argues that they are cautions rather than strict entailments of images (ST I-II, q. 100, a 4). Aquinas’s epistemology begins from the senses and religion and faith are no exceptions. We first encounter the divine in sacrifices and games (ST II-II, q. 94, a. 1), he argues, not in the “pure mind” (ST II-II, q. 94, a. 2): echoes of Huizinga! Citing Aristotle’s Poetics, Thomas notes that humans have a natural delight in representations (ST II-II, q. 94, a. 4) but, following both Aristotle and Basil, Aquinas insists that the honour given to an image reaches to its prototype (ST III, q. 25, a. 3).

Here are two striking comments from Thomas:

“… to adore the flesh of Christ is nothing else than to adore the incarnate Word of God: just as to adore a King’s robe is nothing else than to adore a robed King. And in this sense the adoration of Christ’s humanity is the adoration of “latria” (ST III, q. 25, a. 2).

And:

“… no honour or reverence is due save by reason of a rational nature. And this in two ways. First, inasmuch as it represents a rational nature: secondly, inasmuch as it is united to it in any way whatsoever. In the first way men are wont to venerate the king’s image; in the second way, his robe. And both are venerated by men with the same veneration as they show to the king.”

Why this talk of clothes? Why venerate the king’s robe? Thomas stands in that long line of thinkers stretching from Plato to Lord Shaftesbury who think in terms of ascending scales of graciousness and participation, with the physical lifted and made glamorous and luminous by its being expressive of that which is prior and higher, and in the case of a monotheistic metaphysics, personal. Here, Thomas argues that fine clothing, far from an impediment to worship of God, helps elevate our minds to God: the thesis of Veneration & Refinement!

If I had to boil down what I take to be the difference between Professor Kass and Aquinas it is whether there is an analogy that links the human and divine. Some metaphysics rely on univocity, that human and divine are basically one (Spinoza and Hegel, for example): others on equivocity, that human and divine are radically distinct (a tendency in Augustine and Professor Kass, perhaps). Aquinas’s metaphysics relies on the analogia entis (the analogy of being) and this comes into play here: there is an analogy – and I stress an analogy rather than a type-on-type patterning – between our obligations in human community and duties to God (cf. Chapter 8 of V&R on Przywara and my post http://www.ethicsoffashion.com/trans-humanisms-false-hope/).

A final quote from Aquinas:

“Now in order that any man may dwell aright in a community, two things are required: the first is that he behave well to the head of the community; the other is that he behave well to those who are his fellows and partners in the community. It is therefore necessary that the Divine law should contain in the first place precepts ordering man in his relations to God; and in the second place, other precepts ordering man in his relations to other men who are his neighbors and live with him under God” (ST I-II, q. 100, a. 5).

The veneration of the robes of queens and kings is analogical to the veneration of religious statues and relics and both are deferential gestures upwards to offices and persons that exceed their embodiments. To use terms from scholasticism, human being is an obediential potency (potentia obedientialis) to a sacral universe (Przywara, Analogia Entis, p. 306). There can be strange gods but not every artifact imaging God counts as a strange god. God creates out of graciousness and this objective ethical and aesthetic fund furnishes a sacral universe natural and artifactual.

Aquinas argues that the Decalogue is “the essence of justice” (ST I-II, q. 100, a. 8) – a justice sustained by ethics and aesthetics – so we must be deeply grateful to Professor Kass for helping to shape our thoughts about how we can live well together.