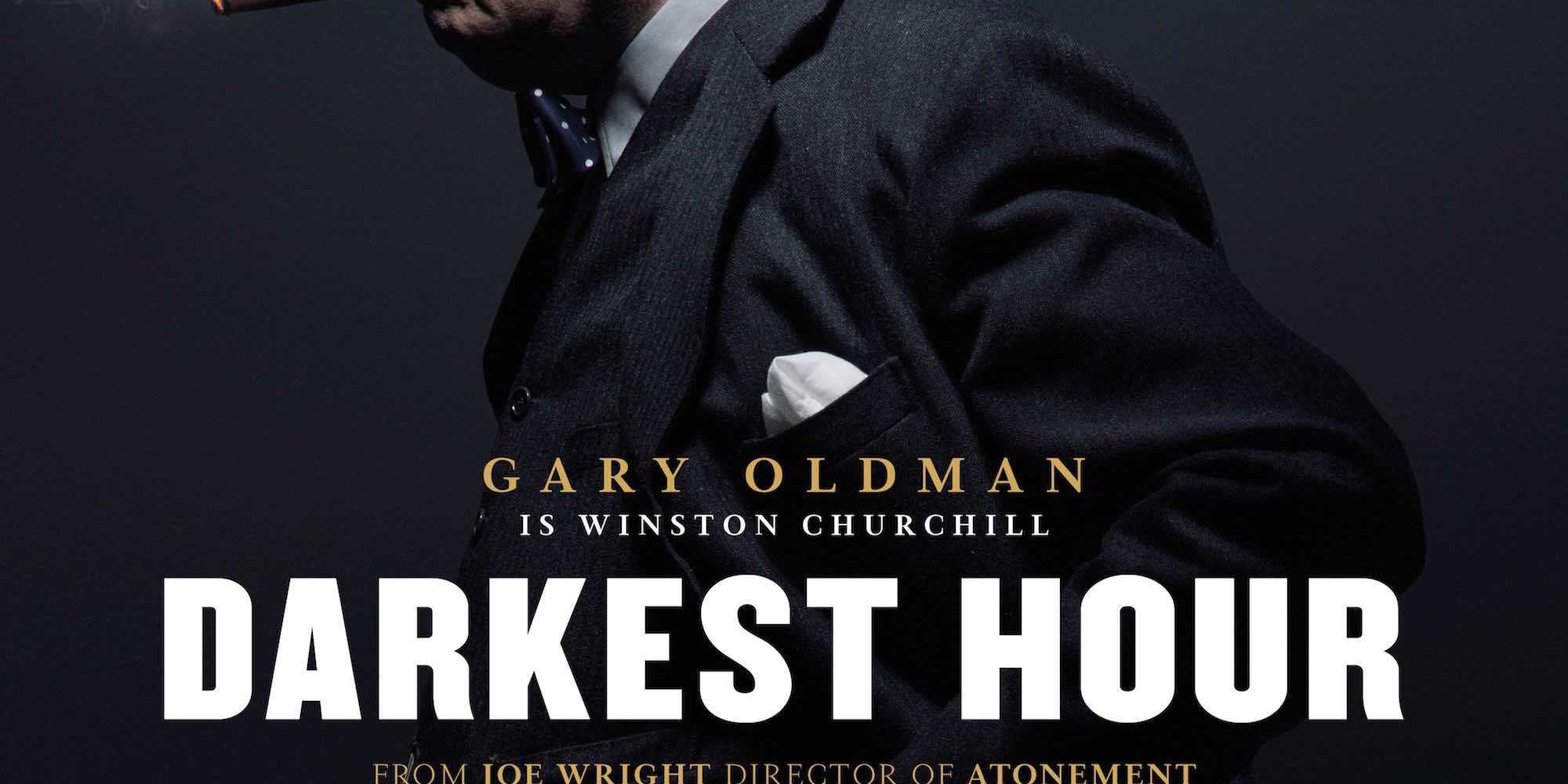

The new Churchill film tracks the hesitancy inside the British establishment on whether to wage all out war with Hitler or to cede to a pact with him. The film is certainly correct that many wished to make a deal with Hitler. Churchill was one of the few who saw the threat clearly.

V&R Chapter 7 is dedicated to the moral and political theory of Aurel Kolnai. He too saw the threat clearly and wrote a massive 700 page book to convince the Anglosphere that all out war was necessary. Below is my introduction to his classic War Against the West and anyone interested in the thoughtscape of Nazism would enjoy reading Kolnai’s accessible, albeit massive, book.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Living in Vienna through the 1930’s, Kolnai once diagnosed a stomach ailment he suffered as morbus fascisticus. In Western countries, many were attracted not only to fascism but Nazism, but many, many more lived in dread of the thought of war renewed. Much of the establishment had fought the First World War, and we can surely understand why it wanted to believe that the growth of National Socialism would not end apocalyptically. Looking back, with all that we now know, it is obvious a fuse was lit and catastrophe inevitable. At the time, Aurel Kolnai (d. 1973) did as much as anyone to warn the West of its doom.

Just as criminal profilers sketch serial killers to try to predict their next steps, so Kolnai sought to distill for the establishment the psychological, moral, and political profile of National Socialism. Aurel Kolnai’s 1938 The War Against the West (WAW) – described by German social theorist Axel Honneth as “ground-breaking” – is surely the most detailed, analytical documenting of the thought-world of Nazism by a philosopher. His profile of the Nazis convinced him that the West had to go to war. Few were willing to listen (recall the United States did not join the war for over two years, not until just before 1942). Today, we tend to think of the Second World War as a matter of moral clarity but its heroes, people like De Gaulle and Churchill, it must be remembered, came to power as hardliners: they were thought suspect because overly indifferent to possible compromise with Hitler. Into the war itself, Lord Halifax and others raised the possibility of compromise with Hitler. Shades of today, some even thought that compromise and radical variety was built into the very meaning of democracy, a position Kolnai wholeheartedly rejected.

WAW was mentioned in a House of Lords debate and praise given by Lloyd George, who had been the Prime Minister of England in the First World War. Yet in 1938 there was no declared war, so what was the Nazi war against the West? In some quarters, people wondered if Nazism was a justified criticism of the West, a reform movement perhaps, or even a revival of the West. At issue, Kolnai believed, was not straightforwardly the open combat to come but a revolutionary assault on the value structure of the West: its moral, political, metaphysical, and cultural convictions and tendencies were all put in dispute by National Socialism (311). As a revolutionary movement it was peculiar, however. Mussolini’s formula for fascism: “Liberty of real man: the liberty of the state and of man in the state” (124) was far outstripped by Nazism’s “weird idealism of tyranny” (125). Forsthoff announced uncompromising struggle “against liberty as a postulate of the human spirit” (107) and, in Kolnai’s gloss, Gogarten’s self-knowledge concludes: “A state rid of the haut-goût of evil would no longer be palatable to him” (127).

Aurel Kolnai was born in 1900 in the twilight years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A native of Budapest, he was an eccentric philosopher and teacher. His eccentricities began at a young age. As a youth during the First World War, he sided with the Allies: he was a precocious child, an Anglophile already influenced by English writers, especially Chesterton.[1] His eccentricities increased when at age 26 he converted to Catholicism – he was born into a highly assimilated liberal Jewish family – and changed his name from Aurel Stein to Aurel Thomas Kolnai. He was never enamored of German culture and thought its influence on the Austro-Hungarian Empire a disaster. This distance helped him cast an accurate eye on the monster rising in Germany when so many others failed. Already the author of three philosophy books in German, Kolnai nonetheless wrote WAW directly into English.[2] He wanted the Anglosphere to go to war against Hitler and thus wrote page after page to demonstrate just how very weird, malign, and thrilled by the catastrophic was Nationalism Socialism. In a letter, Kolnai explains that the massive size of the book was a conceit, “the Kunstform appropriate” to the monumental threat offered by the Nazis.

In intellectual circles today, Kolnai is best known for his seminal contributions to conservative theory in the post war years. In 1938, however, he was a journalist attached to the Christian Left. [3] Victor Gollancz, another member of the Christian Left, published the book in a somewhat austere volume of The Left Book Club.[4] Though a man of the Left, in a remarkably balanced way, Kolnai is careful to parse the political options on the Right: he distinguishes conservatism and reaction from Nazism, and Nazism from fascism. Conservatism tries to protect still existing pockets of privilege from erosion by progressivism whilst reaction tries to resuscitate abolished privilege (107). Nazism, however, contends Kolnai, aims at a root and branch remaking of society, comparable in ambition to the French Revolution. A thread running throughout all 700 pages of WAW is that Nazism celebrated vitalism independently of all ennobling values that control and elevate our drives. National Socialism aimed to re-primitivism the West.

National Socialism sought “a backward leap across the ages” (122):

negating, over and above liberalism, Christian civilization as such (the breeding-ground of Modernity and Progress), as well as the Faith which has informed it, together with some if not most of its sub-soil in Greco-Roman antiquity; and groping back, in its quest for ‘rejuvenating” anti-modern traditions, across the Prussian glory of yesterday and the more brutal aspects of the German Middle Ages towards the barbarous world of Teutonic heathendom – not without a side-glance, in my opinion at any rate, at Hindu racialism and caste religion.[5]

This is what distinguishes Nazism from fascism. Both are subversive but essential for Kolnai is whether either offers any shelter to the abiding values of civilization. However mangled, ordinary civilizational values find a degree of shelter in the narrowed spaces still left to persons in fascist politics. Having moved race to the absolute centre of its politics – Kolnai speaks of a “religion of race” (122) – Nazism reduces persons to elemental forces and rids them of will, thought, autonomy, and eccentricity. In consequence, the delicate spanning of personal appetite and civilizational offerings was eliminated in Nazi Germany. At stake in the war against the Nazi is, most fundamentally, the survival of human personality. In the writings of a Nazified nationalist, Edgar Jung, Kolnai discovers an astonishing lament: “Fascism, in virtue of its Latin roots, is still deeply involved in individualist ways of thinking” (129).

The book has a distinctive method. Kolnai picks out broad topics dear to the Nazis, e.g. fascination with race, cult of the body, or the eroticism of military life, and then gathers under these headings dozens and dozens of quotes from Nazi writers; interjecting commentary, he mostly allows the Nazis to speak for themselves. Kolnai literally collected Nazi literature as it was being handed out in the streets and cafes of Vienna. This method was also dictated by Kolnai’s philosophical conviction of the power of phenomenological analysis. As a student, Kolnai had been a minor part of Freud’s Vienna Circle but in 1925, and in the presence of Freud, Kolnai made a public commitment instead to phenomenology.[6] As Kolnai saw the difference, psycho-analysis is fundamentally about reducing civilization to dynamic vital drives whereas phenomenology is a deferential observation of the values and structures deployed by societies and civilizations. A decade later, Kolnai was even more sure of his stance: the Nazi fascination with vitalism has been a long time brewing in German intellectual circles, dating deep into the nineteenth century philosophers of the will.

Although he mostly allows the Nazis to speak for themselves, WAW does express Kolnai’s Leftist sensibility at the time. This is reflected in the book’s thesis: Nazism is more anti-Western than Bolshevism and “fundamentally opposed” to Liberalism (22; 96-97). By the end of war, Kolnai had morphed into a brilliant conservative theorist. His theoretically rich “Privilege and Liberty” appeared in 1949 but it is his provocative 1950 “Three Riders of the Apocalypse” that most pointedly takes up the themes of WAW: only now his thesis has changed significantly. In 1950, Kolnai argues that the three modern mass regimes – Nazism, Communism, and Progressive Democracy – are linked as a three-headed monster having a single body: “emancipated Man.” Each, albeit to different degrees, is infected “by the virus of subversive utopia bound for a totalitarian goal” (PL, 108):[7] Marxist-Leninism, though, offers “that most genuine and powerful brand of Totalitarianism” (PL, 105). Soviet totalitarianism, he thought, accepted the West’s values but callously betrayed them. Communism sought to use the West’s scientism to launch a pervasive, thoroughgoing transformation of nature. For this reason, Kolnai ultimately came to see Bolshevism as the more complete totalitarianism: concluding that the scientism of Communism resulted in the fullness of the human being’s “self-enslavement,” outstripping even Nazism’s spiritual barbarism (PL, 106).

As a convert to Catholicism, Kolnai was horrified to see Catholic intellectuals hold their noses and find common cause with Hitler (154; 258-63). WAW spends significant time teasing out the place of religion in Nazism. Many theologians of various denominations welcomed National Socialism as an anti-utilitarian, anti-Liberal, and anti-Communist movement, believing that they could flush away its most poisonous aspects and ultimately re-direct the movement to higher spiritual fields.[8] Kolnai warns again and again how utterly foolish any compromise by religious or political authorities with the Nazis will prove. He points out that Nazi writings betray a particular animus to the Ten Commandments (288), which Aquinas argued contained the precepts of the natural law (Summa theological, II-II, q. 100). The hope of National Socialism was re-primitivism, a revolution bent on deflating civilization itself. Some Nazis thought themselves Christian, others pagan, and in Kolnai’s summary National Socialism offers “Teutonic religious opposition to the Roman and Western world” (13).

Other Nazis offered astonishing religious inversions. Stapel declares that “Jesus and the Virgin Mary of the Germans are Germans” (266). Goebbels explains that the great Commandment “love thy neighbor” entails “I cannot love him unless I hate his enemies” (243). Blüher argued that Christianity was a refined form of anti-moral paganism fostering secret groups of men, the builders of the state, whose intensity of shared brotherhood counterbalances the distraction, compromise, and evasions of family life (75-79). Redolent of Burke, Kolnai observes it is the ethos of family that is in keeping with parliamentary self-rule. Blüher was equally critical of civilian and bourgeois life, the man of fashion, and the mutuality assumed by contract law. More common was the opinion of Rosenberg, keeper of Party lore, that Christianity and humanitarianism are “nerveless ideas,” having nothing to do with “Nordic cells of soul” (34-5). Far preferable to Jesus is Wotan, a landgeboren god of the same kin as his people, not requiring veneration of “a holy Sepulchre in a far-off land” (244). Christ, by contrast, offers the lamentable idea that there could be “an immediate loyalty between man and mankind” (103).

Besides phenomenological method, Kolnai’s other intellectual commitment at this stage was personalism. A school of thinking especially strong in French Catholic circles, Kolnai defines personalism: “We believe that true community can be based only on personality, which is the irreducible core of human existence, with its susceptibility to moral elevation” (65). Nazi celebration of tribe swallows this idea just as surely as it swallows the idea of a common humanity. Punishment, Rosenberg declares, is not linked to persons transgressing objective standards but “the ejection of foreign types and of essence that is not kindred” (36). A modern commentator on Nazism has spoken of the Nazi commitment to “a rupture of species” (Rolf Zimmermann) and Kolnai glossing Gogarten explains: “there is no being `in oneself,’ only a being `for one another or against one another’” (70; 294-95) Throughout the text, Heidegger and Schmitt are roundly criticized for fostering such formulations. As well as subverting the ideas of personality and common humanity, Nazism was bent on weakening the idea of nation.

The nation state posits limits but National Socialism exhibits dual intensifications. Hielscher dreams of “the chain of inwardness” being brought into union with the “chain of power.” Meister Eckhart, Luther, Goethe, Nietzsche fused with Theodoric, Henry VI, Gustavus Adolphus, Frederic the Great, and Bismarck (37): “the soul merged unconditionally in the state, the state an epitome of sacredness.” The Nazi state is not built on nation but race, manifesting itself as tribe plus empire. Tribe demands intensification of loyalty, a band of brothers (the männerbund or manring). Tribe conceived as a race of masters demands mastery of others, thus an intensification of imperial ambition and expansion into space. This vitality naked of restraining values of person, nation, human kind, or transcendent God, evokes Kolnai’s brilliant analysis of disgust.

Husserl published Kolnai’s On Disgust in 1929 and it continues to influence contemporary research into the aversive emotions.[9] Salvador Dali and Georges Bataille were inspired by the text’s central thesis that the disgusting is life out of place; life unrestrained, leering and smirking, proboscis-like, feeling its way toward one. Kolnai argues that disgust is basic as a moral disvalue. Immorality is most strictly infractions against persons and disgust leaps across all the fields of discretion that civilization opens for the free movement of personal interaction. Tribal unity, what Kolnai calls, “tribal egotism,” simultaneously submerges distance amongst persons and precludes others from being persons.

For varied reasons, National Socialism is a moral, political, and civilizational disvalue. In a number of places, Kolnai credits Nazism with asking probing questions of the West and its politics. The answers it offers are to be utterly rejected but Kolnai concedes at least the validity of some of its questioning and Nazism poses an intellectual problem for Kolnai. As mentioned, Max Scheler influenced Kolnai. Scheler was an advocate of value theory: a realist theory of morals arguing that we have ready access to discrete, extra-mental value-tones: e.g. if I say `peach’ you now have the taste and smell of a peach clear to your mind, and not that of a lemon. We can replicate this value tone in lip balm, fizzy pop, and even gin, once we have distilled it into a chemical formula. Morals have a similar value standing: [10] if I tell you a story about how I met a benefactor or about a civil chat I had with a man on a train whose conversation suddenly flashed with malice, you have clear to mind a range of value tones that make these encounters comprehensible. The ontological standing of values minimizes the grip of the state: it props up ideas like the independence of social relations from the state or a collective response open to all humans to shared value experience.

Scheler argued, and Kolnai agrees, that values make an appeal whilst disvalues are aversive. The problem is how a nation fell under the spell of aversive qualities. To be sure, this problem is not unique to value theory: every ethical theory quakes before the malignant potency of Nazism. Of course, the disvalues were carefully choreographed in theatre (220)[11] and in many ways cloaked and hidden from the generic population, as explained by Hannah Arendt.[12] Nonetheless, the puzzle forcefully remains: disgust somehow lost its protective moral power.

Re-published here is a little under half the book. Latter parts of the book include plenty of philosophy but also Kolnai reflecting on Germany’s standing as an east European power, pages on geo-politics that now have more of an historical interest. Amongst parts left out, Kolnai treats in detail Nazi economic ideas and offers much more about National Socialism’s race politics.

In a retained but challenging section of the book, Kolnai considers Hitler’s own writings. Historians of the period will find these pages fascinating for Kolnai argues that “many of the more subtle and morbid Nazi conceptions of religion, culture, mode of living, etc. would make no appeal whatever to Hitler” (135); for, on his reading, Hitler was devoted to the “worlds both of romantic nationalist heroism and hard, matter-of-fact capitalism” (136). He acknowledges the deft political strategy of Hitler to both convince Germany’s economic elite that democracy must entail large state appropriations of private property and convince the mass of proud nationalist Germans that no mere conservative or authoritarian government short of the absolute power of the Führer could utterly root out international Leftism. For Hitler, the struggle was always about democracy and, of course, democracy, in his telling, was a Jewish innovation. Hitler thus was clear-eyed about his political goals but transferred the field of contest to race (135-37).

Wed this cynical politics with the heady-brew of Nazi fantasy already outlined and the fuse is lit. Political malice is guaranteed when the tribe (Volk) believes itself beset:

The Political Soldier of the new Reich detects the foe of His Reich in ever disguise, because he carries the Will of his State in his blood: with his instinct of a fighting race, he traces the adversary who approaches him, however camouflaged as a friend (G. Günther).

Who the foe in disguise is the Führer reveals. The Führer is not a monarchical, aristocratic, democratic, or conservative political principle. Monarchical and aristocratic politics are constitution bound, democratic popular decision is diffuse, and conservatism tied to established offices. Utterly different, the Führer principle is mystical, for the Führer “has a firmer hold on my inmost striving than has my own personality in its isolated self” (150-51). “There are no longer any private people” (Ley) (169). My personal sovereignty suspended, the tribe’s will is one with government, in the person of “Mein Führer.” “In this man’s mortal frame, the original Germanic stature is incarnate” (151). The vitalism of the tribe ensures that constitutional guardrails are abandoned, democratic will has no anchor in the varied wills of a great plurality, and the aloof office holder is now my chieftain and guide. Hitler bemoaned monarchy as a principle of stability (175) and Party theorist elaborates Feder: the Führer must have a “somnambulistic feeling of certainty” for inward drive is decisive, and whilst severe and hard upon himself, to others… not mildness and mercy, but the exercise of “the art of hating” (151-52).

Most fundamentally, National Socialism was a valorization of vitalism: “Thou art but a tool of Nature, a station of transition and decay destined to serve higher ends. Life lives on life!” (Haiser). A fusion of body worship and a militarized soul (190), combined with a fusion of race and revelations from a chieftain more intimate to self than one’s own person. This dynamic brew was hitched to machines, technological advancement, and diligent government but not to ideals of objective truth, impartiality, fair play, kindness, beauty, equitable distribution of goods, and a balance between ordinary pursuits and the life of the mind. No deference was paid to the long inheritance of Western manners and mores and a decision against Christian dignity was made in preference to Pagan abandon to ecstasy and despair (210-11). WAW documents that emancipation from the West’s establishment is nothing less than re-primitivism.

[1] A. Kolnai, Political Memoirs (Lexington, 1999).

[2] Under the auspices of the Hannah Arendt Institute, Wolfgang Bialas, a German scholar of the Nazi period, translated this hefty book into German and chased down all the sources Kolnai used (Der Krieg gegen den Westen [Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015], 763 pp.). Funded by the German government, it took Bialas four years to complete the edition.

[3] F. Dunlop, The Life and Thought of Aurel Kolnai (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002).

[4] A. Kolnai, The War Against the West (London: Victor Gollancz, 1938).

[5] “Three Riders of the Apocalypse,” A. Kolnai, Privilege and Liberty and Other Essays in Political Philosophy (Lexington, 1999), p. 111.

[6] “Max Scheler’s Critique and Assessment of Freud’s Theory of Libido,” Politics, Values, and National Socialism (Transaction, 2013).

[7] I discuss Kolnai’s observations about the totalitarian aspirations internal to contemporary humanitarianism in my Ecstatic Morality and Sexual Politics (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005).

[8] For an interesting contemporary debate about this, see A. Pidel, S. J. “Erich Pryzwara, S. J., and “Catholic Fascism,” Journal for the History of Modern Theology 23: 1 (2016), pp. 27-55.

[9] A. Kolnai, On Disgust (Open Court, 2004).

[10] V. Vóhanka, “The Nature and Uniqueness of Material Value-Ethics Clarified,” Ethical Perspectives, Vol. 24 (2017), pp. 225-58.

[11] G. Agamben, The Kingdom and the Glory (Stanford University Press, 2012).

[12] H. Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem (Penguin, 2006).