This post is really Part II of my recent post – Why do women buy Kate Middleton’s nose? That post took up Tim Gunn’s claim both that designers have contempt for fuller figured women and that no technical reason exists why designers cannot beautifully dress their bodies.

Likely Tim Gunn’s comments reflect some of the horror he must have felt on his TV programme, the student fashion competition, Project Runway, where the “design for real women” challenge typically resulted in tears and mortification all around.

In that earlier post, I referenced Lord Shaftesbury’s ethical theory rooted in our experience of the beautiful: an experience he thought dependent on a set of value tonalities transcendent to, yet shaping, our world. Echoing Plato, he thought that the harmonies and poise of bodies and acts provoked by the value tonalities relied on number.

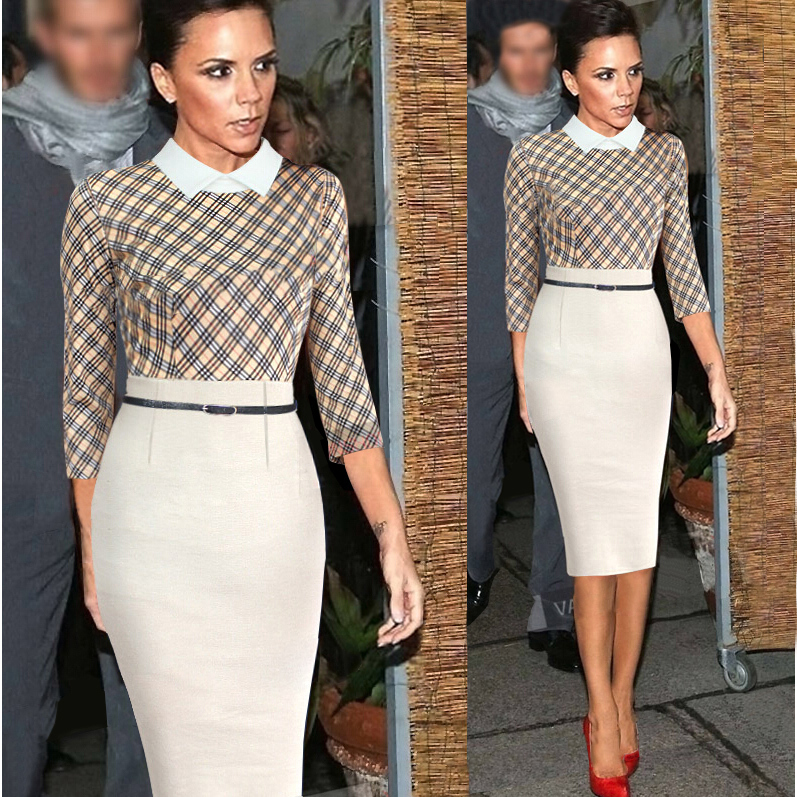

This theory explains well why Victoria Beckham (VB) looks so fabulous in the picture below and why Tim Gunn is surely right to criticize. If bodies are volumes, and if design relies on geometry, then Gunn is right that no technical impediment can exist.

At many points in Smith’s writing the influence of Shaftesbury is evident but his own aesthetic theory of morals departs somewhat from that of Shaftesbury’s. He is likely even more supportive of Gunn’s position. Shaftesbury would thrill to Victoria Beckham’s look but Smith demurs. VB’s 2016 collection was noted for its nod to the corset (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/fashion/new-york-fashion-week/victoria-beckham-new-york-fashion-week-aw-2016-front-row-celebri/).

But Smith has this to say:

“Some of the savage nations in North-America tie four boards round the heads of their children, and thus squeeze them, while the bones are tender and gristly, into a form that is almost perfectly square. Europeans are astonished at the absurd barbarity of this practice… But when they condemn those savages, they do not reflect that the ladies in Europe had, till within these very few years, been endeavouring, for near a century past, to squeeze the beautiful roundness of their natural shape into a square form of the same kind” (TMS, 199).

Smith prefers “the beautiful roundness” of a woman and her “natural shape” to the hyper articulated, radically pulled together look of VB. In our quote, he puts square and round in opposition so it is not that he is distancing himself utterly from the geometry and logic of Shaftesbury’s theory but he does mean to soften it.

Besides Shaftesbury, an influence on Smith’s aesthetics is the eighteenth-century French Jesuit, Claude Buffier (d. 1737). Smith explicitly builds his theory from a consideration of Buffier, who argues that the beautiful is what we customarily see. Smith gives the example of a nose and observes that we do not customarily see a perfectly triangular nose or one that is circular. We see rather noses that are a mean between these extremes.

Designers do not design clothes for women one customarily sees, rather, to follow Smith’s example of the nose, one or other of the geometrical extremes. On Smith’s account, and surely to the utter horror of designers, they are not currently dressing beautiful women. Runway shows, Smith is committed to arguing, are value delusions. Perversions of beauty.

Perhaps I’ll return to Smith’s account of value delusion – and maybe compare it to the more famous accounts offered by Nietzsche and Scheler – but for now it is enough to note that Smith would join with Gunn in pointing out the immorality of designers’ attitude to the customary woman.