The anarchist, Proudhon, argues that Rome fell because she was incapable of changing her “objects of public veneration.” Rome’s gods, he says, were blood and luxury. The Empire crumbled when her gods, who had served her well in the past, proved inflexible amidst new circumstances, not the least of which was a man, a man “calling himself the Word of God.” This new god provoked a war, “a war between executioners and martyrs,” that ended with a revolution in religion and the violation of Rome’s “most scared rights.” Blood and luxury were “replaced by a more austere morality, and the contempt for wealth was sometimes pushed almost to deprivation.” A fine example of this contempt is recounted by a fifth-century cleric:

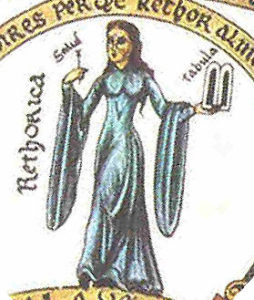

Having entered the church to perform a prayer, we found at the door a dyed curtain upon which was depicted some idol in the form of a man. They alleged that it was the image of Christ or one of his saints, for I do not remember what I saw. Knowing that the presence of such things in a church is a defilement, I tore it down and advised that it should be used to wrap up a poor man who had died. But they complained, saying, `He should have changed the curtain at his own expense before tearing this one down.’[1]

2

However, our age, says Proudhon, is an age of “monsters.” Theologians betrayed the promise of that distant revolution speculating absurdly on the birth and origin of the man “calling himself the Word of God.” Requisite was practical administration of the social implications of the new morality but, that god abandoned, the gods of Rome reappeared only now twisted hideously. Christianity monstrously birthed new gods: “the privileges of birth, province, communes, corporations, and trades; and, at the bottom of all, violence, immorality and poverty.”[2] To what degree is fashion one of these new monstrous gods?

3

There is little room for dispute about what are our “objects of public veneration.” Many in the West do not go to church though many millions still do, yet all are united in their fascination with design, fashion, and celebrity. Products of commerce and privilege are celebrated equally in the glossy pages of the Financial Times’ magazine, How to Spend It, and the Jay-Z/Beyonce song, “Upgrade U.” The pop video opens with a massive diamond in Beyonce’s mouth and amidst a surfeit of images of luxury, Beyonce’s remarkable singing voice explains how she will support her man and through hard work better his condition. Meanwhile, Jay-Z promises diamonds on rings as big as tumors so that Beyonce’s hand won’t actually fit into her handbag. It doesn’t much matter whether one is a “mall rat” or a badly dressed university professor glorying over his iPad purchase, our deference to design objects is near total.

4

Near, but not, total. For Proudhon is right: our objects of veneration are monsters. The Christian revolution expanded the boundaries of justice and Proudhon expresses confidence that now justice will never return to Rome. Unlike Rome’s breezy indulgence in gore and glamour, we hesitate. It is now impossible not to feel a certain tug whenever sentiments are expressed like that of Luke 16:19-31: the rich man in hell, who used to dress “in purple and fine linen,” beseeches Lazarus, a man “covered with sores.” Imagine only: after watching the “Upgrade U” video, a man who “fancies his chances” goes into a bar, a woman smiles at him, he approaches, she seems impressed, and he then asks whether she could do for him what Beyonce says she can do for Jay-Z. Few pick-up lines work, I imagine, but this one is a disaster. Oddly, people do want to be appreciated for who they are as persons not for how much they work, and not for whatever design enhancements they might be sporting. Yet the whole is curious: the enhancements catch the eye, at cocktail parties everyone asks, “What is it you do?” and though the person is elusive, personhood is also stubborn. Personhood is that austere place, cemented in our consciousness by Christianity,[3] which dethrones wealth and explains why Proudhon is sure that now justice will “never return to its original limits.”

5

Whether a Christian or not, a partisan of the Left or the Right, many today are disgruntled, or more, with commercial life.[4] Christians recall the warning of King David that all is vanity and meditate on the warning (question) of Jesus: What does it profit a man who earns the world but loses his soul? Leftists think that money is dirty[5] and eschew business for the non-profit sectors of education, journalism, activist and watchdog associations.[6] Rightists bemoan the collapse of the family and community as labour and capital move ever more quickly globally.[7] Despite the laments, however, the West shows little genuine inclination to shake off the Whig Settlement.

6

Civilisation, refinement in the arts and sciences, is a consequence of commerce, argues David Hume.[8] He writes:

The more these refined arts advance, the more sociable men become … They flock into cities; love to receive and communicate knowledge; to show their wit or their breeding; their taste in conversation or living, in clothes or furniture. Curiosity allures the wise; vanity the foolish; and pleasure both. Particular clubs and societies are very where formed: Both sexes meet in an easy and sociable manner; and the tempers of men, as well as their behavior, refine apace. So that, beside the improvements which they receive from knowledge and the liberal arts, it is impossible but they must feel an increase of humanity, from the very habit of conversing together, and contributing to each other’s pleasure and entertainment.[9]

7

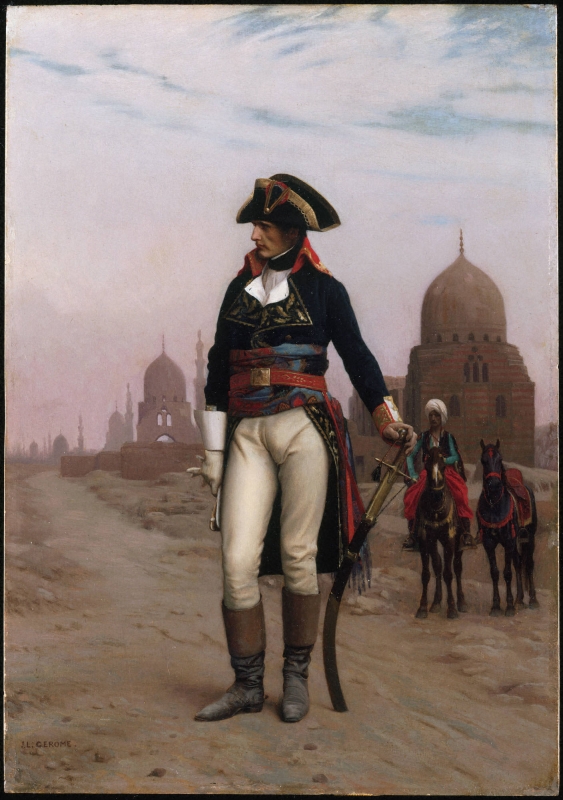

It is the allure of fashion, opulence, and vanity, which incites our “relish for action,” quickness of mind, and our very humanity, insists Hume. Between them, Adam Smith and Hume, the two leading lights of the Scottish Enlightenment, might be said to have established the Whig Consensus. Their argument is dramatic: vanity is the basis of liberty. Turning the moral tradition on its head, they argue that the human appetite for adornment — looking at the beautiful and being thought to be beautiful — is the engine of commerce. Given free rein in fantasy and commerce, vanity will induce new refinements in the mechanical and liberal arts[10] and carry nations out of poverty and towards civilisation. Rule of law is essential as these refinements are only made possible through the use of property. Property holding is basic to adornment — indeed, it maintains our idea of self[11] — and privilege gives owners both an interest in liberty and the means to resist abuses of power.[12] Vanity is the antidote to tyranny, insists Hume. This is the Whig argument that has settled into the Western mind and become a fixed sensibility of her peoples.[13] And not only the West: capitalist China has a remarkable lust for adornment, with a voracious appetite for diamonds[14] and L’Oreal beauty products for men.[15] Chinese women also love Maseratis. Women buy thirty percent of all the Maseratis sold in China: by contrast, women in the West buy only three percent.[16] The jump in China’s adornments is matched by the jump in people’s wealth, health, and rapidly generated social privilege,[17] just as Hume and Smith predict.

8

Who can doubt that the Scottish Whigs are basically correct?[18] Whether you love the music of Sir Charles Avison, Spode china, Gucci, Facebook, or the applications on your iPhone, the benefits of vanity and commerce to refinement and civilisation seem obvious. Hume espoused the Whig argument heartily, Smith, only with hesitation. Smith frequently speaks of the “delusive colours” the imagination is apt to paint a life of luxury (TMS, 51) and his portrait of the ambitious young man fooled by riches, and betrayed, is chilling (TMS, 181). Commercial society is about toil, risk, and anxiety, warns Smith; it is a matter of serving those you hate and deferring to those you contemn; there is little room for dignity in ambition, which Smith terms “heaven’s anger” (TMS, 181). But Smith is convinced a price has to be paid so that the earth can redouble her fertility, as he says, and poverty be alleviated (TMS, 184). Smith’s sober assessment contrasts with Hume’s celebration but neither would much regret Pope Benedict surveying the “civilisation of technology and commerce that has spread victoriously throughout the world.”[19]

9

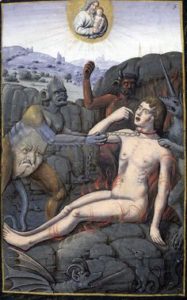

Reflecting on contemporary Europe, Benedict XVI speaks in tones at least as dark as those of Proudhon. He argues that the founders of the EU — Adenauer, de Gaulle, de Gaspari —thought significant continuity existed between the Christian heritage of Europe and “the great moral impulses of the Enlightenment.” Benedict is less convinced, believing that “questions were left open that still await a proper examination.”[20] Whatever those answers, they are not of immediate concern, he thinks, for a second Enlightenment succeeded the Enlightenment, one in which “man as a product is subject to the control of man.”[21] The impetus of this second Enlightenment is to make suffering disappear: the cost of this humanitarian ethic is a new slavery featuring widespread abuse of early human life and human trafficking. Like the slavery of old, this new trade in human flesh defers to commercial impulse.[22] In a startling footnote, Benedict quotes famed biologist, Erwin Chargaff: “Where everyone is free to pull the wool over the eyes of his neighbor as in the example of the free market economy, we end up with a ‘Marsyas’ society, a society of bleeding corpses.”[23] Commercial civilisation is deceitful, and it is the tricks played on one’s neighbour that supports a culture of death.

10

Is Benedict right? In Chargaff’s telling, commercial civilisation is a latter-day Ring of Gyges: blinded by trickery, we are all fakes, and wholesale abuse reigns.[24] Some will respond that Chargaff is wrong: markets only function well when there is transparency. It is easy to imagine that contemporary business is a rough-and-tumble Wild West where the “survival of the fittest” is a daily-tested axiom, but such an image is very far from the truth.

Business tends to welcome transparency to keep costs down, and besides, vast government regulation orders business, legions of accountants ensure that shareholders, and the tax man, know what each company is worth, and tort lawyers are ever-watchful. Another complication for Benedict is Philippe Nemo’s recent thesis about the West. Building on the seminal work of law historian Harold Berman, Nemo argues that the Gregorian Reform, dating to the eleventh century, established the basic framework of law and property that endures today. Commercial society operates within this framework. In Nemo’s telling, Pope Gregory VII sought to Christianize the world in a thoroughly concrete manner and his chosen instrument was Roman law. The task was to infuse the law with the spirit of the Gospel and to bring both to bear on the matter-of-fact realities of ordinary domestic, commercial, and civic life.[25]

11

If our notions of property, contracts, and business organization are a gift of the Gregorian Reform, how can the Pope make common cause with the anarchist? Would it be absurd to ask whether Benedict dissents from Gregory? It is not absurd. Nemo argues that the reform movement was highly contested for centuries.[26] And yet, whatever the difficulties of the Pope’s position, Smith would likely concede that Benedict is right in some sense: Smith does think that delusion is a general condition of fashion and commerce. He writes:

Power and riches appear then to be, what they are, enormous and operose machines contrived to produce a few trifling conveniencies to the body, consisting of springs the most nice and delicate, which must be kept in order with the most anxious attention, and which in spite of all our care are ready every moment to burst into pieces, and to crush in their ruins their unfortunate possessor. They are immense fabrics, which it requires the labour of a life to raise, which threaten every moment to overwhelm the person that dwells in them… And it is well that nature imposes upon us in this manner. It is this deception which rouses and keeps in continual motion the industry of mankind (TMS, 183).

12

How tolerable is it that our lives of fashion and commerce rest on fantasy and delusion?[27] Benedict puts the problem forcefully. He stands in the long tradition of Plato in seeing reason’s access to truth as a form of exorcism. Truth is Christ, and Christ is Logos, thus the mission of the Church, insists Benedict, is to demythologize.[28] “Many deities of the world religions are terrifying, cruel, egoistic, or impenetrable”[29] says Benedict, and with Chargaff, he clearly thinks the god of commerce, vanity, with all its artifice and illusion, its fashion, is no different. “Demythologization is urgently needed so that politics can carry on its business in a genuinely rational way.”[30] Benedict makes common cause with Proudhon: pope and anarchist using political theology to purge what is monstrous within us.[31] Does fashion, as Hume thinks, save politics, or does it destroy?

13

I think that Benedict’s designation of a second Enlightenment, and its use of man as a product to relieve suffering, is well observed. I tried to make an extended argument to this effect in To Kill Another. Benedict makes no formal comment on whether the first and second Enlightenments are formally linked but his agreement with Chargaff suggests he believes the Scots helped foster the contemporary pragmatic conception of man. This is how Tracey Rowland reads Benedict.[32] But what if there is no substantial continuity, and Benedict has conflated commercial life with a different phenomenon, humanitarianism?[33] Does the artifice, illusion, and fantasy of fashion invite the culture of death?

14

Is vanity always a deadly sin? The question is not new. Change one word and we are back at the founding of Western philosophy, with Plato, and his question: Do artifice and fantasy invite tyranny? Famously, Plato answers “yes.” Aquinas did not have any immediate contact with Plato’s Republic but his analysis of demonic possession has startling structural continuities with Plato’s analysis of tyranny. Even so, I wonder if Aquinas’s account of possession and exorcism doesn’t depart from Benedict’s. However startling the continuities with Plato, Aquinas’s use of Aristotle on this matter is more dramatic still. Vanity builds solidarity, argues Aquinas: an argument, I suspect, suggested to Thomas by Aristotle’s response to Plato in the Rhetoric. This reliance is dramatic because Aristotle’s reply to Plato seems an odd one for a Christian to acknowledge: status.

15

My suggestion is: (property) possessions are one antidote to possession. If my interpretation of Aquinas is correct, what new things do we learn? Since status in Aristotle is a matter of the “emotions,”[34] we learn that the emotions hold a particular structural importance in Thomas’s thinking, and this clarifies the character of Thomistic natural law ethics. The role Thomas assigns to the emotions pulls his thinking towards the Scots and the Whig Consensus.

Plato’s question — What is the ontological, moral, and political standing of vanity and fantasy? — is the question of fashion.

16

Plato’s condemnation of fantasy is thoroughgoing. The Republic begins with Socrates down at the port of Athens to watch the arrival of a new god. The Thracians have gifted Athens with the goddess Bendis, a sort of Baccanalian deity. Unsurprisingly, the young men of Athens have gathered waiting for the party to begin; they are full of expectation and have likely spent the day imagining with one another what will happen at the night’s revels. The dialogue opens with Socrates, having already turned his back on Bendis, walking, as Plato puts it, “back home.” Socrates does not reach home, however, for some of the young men chase after him, and ushering him to the home of Cephalus, an evening of debate begins.

17

The night is spent in philosophical discussion with the young men skipping the party and Socrates never making it home. Neither with the gods of Thracia nor those of Athens, Socrates defers to a world parallel to ours, the world of the Forms, as he draws the young men away from fantasy and towards reality. The discussion begins with a series of conversations about false allurements: sex, money, war, competition, and vanity. The book soon transitions to thoughts about a model republic yet almost immediately the essential issue emerges: How to manage a republic once luxury is permitted? The bulk of Plato’s Republic does not concern “the true” society but how to cope in a republic where there is deception, illusion, and fantasy fostered by the arts in their service of the people’s appetite for luxury (373a-e). Plato’s interest in the opposition between truth and fantasy culminates in his account of justice wherein reason faces a rebellion from the appetites (443a-444b), liberty fails, and the republic becomes a “shop” (557e).

18

Capping his account of justice are Plato’s famous pages on art where he damns the poet as a “charlatan” unable “to distinguish knowledge, ignorance, and representation” (598d). We are asked to consider a father grieving the loss of his child. A true father grieves at home and in public is all composure. The dramatic arts, by contrast, bring grief into public and, as Plato puts it, “in a fond liaison” the arts and emotions transform the republic into a sensuous realm; a potent brew of artifice and emotion squeezing out the austere calm of reason and truth (603b). The republic is then easy prey for the tyrant since only one “in a state to grasp the truth [is] undisturbed by lawless dreams and visions” (572b). Thomistic natural law offers itself as the foundation for the morals and jurisprudence of the republic. The emotions play a significant role in my interpretation of Thomas’s natural law and it is, therefore, especially vulnerable to Plato’s condemnation of fantasy.

19

Indeed, matters look bleak. In a remarkable structural continuity, Aquinas conceives of the devil in terms strikingly similar to Plato’s tyrant. Demons are adepts in fostering “a fond liaison” between artifice and emotion. For devils, says Thomas, “sometimes cause things that do not subsist in the external world to appear to human beings” (DM, 506). Devils “fashion forms in the imagination” (DM, 508) and cause “unreal things” to appear (DM, 506) by their artistry: “And devils can in this way also present new things to human beings’ imagination by different compositions of movements and forms, certain seeds, as it were, hidden in sense organs, whose potential devils know.”[35] Demons do not, in Thomas’s telling, actually enter the bodies of the possessed. Rather are they rhetoricians who through persuasion manipulate the emotions (DM, 156). Thomas’s expressions aptly apply to the fashion industry. Thomas adds: “And so we call devils tempters since they learn through the actions of human beings to which emotions the human beings are more subject, so that the devils may thereby more effectively impress on the imagination of those individuals what they intend” (DM, 156). Devils accomplish possession by observing our emotional life and then crafting a fantasy out of the contents of our imagination that will trigger our emotions.

20

The phenomenon of possession in Thomas then is remarkably similar to Plato’s mechanics of tyranny. What of exorcism? A clue lies in an interesting formulation Thomas has for God. In Plato’s terms, Aquinas boldly casts both God and Satan as poets. Thomas says that “the devil offers sin to human beings as a persuader,” but good angels are also persuaders, as is God. Though God can choose to move the human will internally, God moves the will “as external persuader” (DM, 154).

20

And thus Thomas’s formulation suggests another remarkable structural continuity. Aristotle’s Rhetoric offers an immediate and striking dissent from Plato, with Aristotle arguing that the emotions and fantasy block tyranny. This is the Whig argument of Hume and Smith: vanity is the antidote to tyranny. And, I think, pretty much the same can be said of Aquinas: vanity can build solidarity, and in building human community forestall tyranny and the culture of death.

21

In the Rhetoric, Aristotle states: “men are for the most part status loving.”[36] For Aristotle, status is: being of good family, having numerous and creditable offspring, and property.[37] Tyrants would remove each of these but, inevitably, belittlement generates resentment, which provokes revenge.[38] Before the act of revenge, there is a fantasy: “Men dwell on their revenge in their thoughts. Thus the imagination arising on these occasions produces a pleasure like that of dreams.”[39] Tyranny is thus impeded by fantasy and emotion. Why does Aristotle not share Plato’s anxiety that emotion is the root of tyranny, too?

22

All political rule is inevitably always a matter of managing fantasy and emotion. Plato thinks the republic’s salvation ultimately lies in the intuitive perception of the forms, the exactitude of measurement (602d), but Plato’s position, for Aristotle, betrays an ontological mistake. What concerns political rule are events and matters “where precision is impossible:”[40] on military matters, for example, Aristotle insists the ruler must leave the city, travel the countryside, and look at the lay of the country’s guard towers.[41] Fantasy and emotion also resist precision, and persons, argues Aristotle, are much given to fantasy. Cataloguing pleasant things, besides revenge, Aristotle speaks of: winning “for it produces the imagination of superiority;”[42] status and reputation “as to each enjoyer of them there occurs the imagination that he is of a kind with the serious man;”[43] and even shame, since it is an imagining of what others are thinking about you.[44] Aristotle’s yardstick of rule is not therefore Plato’s “measuring, counting and weighing” (602d) but rather evidence, witnesses, a standard of reasonableness, linking facts into a story, and thus poetry and performance.[45] With these means, fantasies can be ordered and emotions ruled. Can fashion play this role?

23

Aristotle seems to suggest a formula: where the subject matter is imprecise, effective rule relies on imprecision. He writes: “Unlike some experts [Plato, certainly], we do not exclude the speaker’s reasonable image from the art [of rhetoric] as contributing nothing to persuasiveness. On the contrary, character contains almost the strongest proof of all, so to speak.”[46] Does fashion harmonize reason and artifice?

24

Belief in God as the summation of our lives is, for Thomas, an example of Aristotle’s matters “where precision is impossible:” for, as Thomas explains, “the necessity of this connection [between God and human happiness] is not fully evident to human beings in this life, since they do not in this life behold the essence of God.”[47] Unsurprisingly then, God’s communication in Scripture and the Church adopts the yardstick familiar from Aristotle: evidence, witnesses, a standard of reasonableness, linking facts into a story, poetry, and performance.

25

In Aquinas, truth appears with rhetoric and the leading attribute of the yardstick is sociality. This is also unsurprising, since, argues Thomas, we are comparative creatures: compared to God in the first place, secondarily to one another, and thirdly to our own sense of self. Thomas concedes the legitimacy of status, therefore. Not all pride and vanity is good — obviously — but Thomas argues that some is. Pride prompts humans to seek excellence amidst the goods of this world and vanity provokes humans to seek excellence in the regard of one another, attaining the good in imitation of each other. The matter is delicate, but vanity can build excellence and solidarity.

26

If I am right about how Aquinas relies on Aristotle’s Rhetoric, we must conclude that the stark image prophesying the Messiah at Isaiah 53 is, to Aquinas’s mind, a true image of Christ but not, in any straightforward way, you and me. Lord Acton, the English historian, once said that Thomas Aquinas was the first Whig. Some theologians find this preposterous, yet Aquinas does edge towards Smith. Aquinas indulges the monk deluded about the quality of his singing voice and does not reproach the owner proud of her racehorse (DM, 346). When vanity is ludicrous, or when underwritten by genuine excellence, it is harmless enough. When vanity supports varied imaginings of the self that ultimately serve solidarity, Thomas views these fantasies as licit.

27

FOOTNOTES

[1] As cited in T. Thomas, “The Medium Matters: Reading the Remains of a Late Antique Textile,” Reading Medieval Images, ed. E. Sears & T. Thomas (Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 2002), p. 47-48.

[2] P.-J. Proudhon, What is Property? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 24-26.

[3] Philippe Nemo argues that Roman property law eked out the first place for personhood but what a boost it got from St. Paul’s “neither Greek nor Jew.”

[4] The Anti-federalists at the time of the American Founding were mostly skeptical about commerce and cities and saw a significant link between luxury and deceit. See John Danford, “David Hume and the American Founding,” in Recovering Reason: Essays in Honour of Thomas L. Pangle, ed. T. Burns (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010), pp. 285-303.

[5] See the Martin Amis, Money.

[6] Some leftists want to write out of the history books the contributions to modem life made by commerce. Jonathan Israel borders on contempt for the Scottish Enlightenment writing a history of modem civilisation whose benefits we owe apparently to Spinoza and his cultivation of the thinking estate. Here the benefits of modem life have nothing to do with ugly logistics centres, railheads, ports, and such like, and the worry that Spinoza’s monism may have helped usher in collectivism and all its destructive progeny is elided (Jonathan Israel, A Revolution of the Mind [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010]).

[7] See Phillip Blond, Red Tory, and various position papers of his think tank, ResPublica.

[8] Though Wiggins does not treat Hume on vanity and commerce, he dwells at length on the centrality of refinement and civilisation as the glue of his moral theory: D. Wiggins, Ethics: Twelve Lectures on the Philosophy of Morality (Harvard, 2006).

[9] D. Hume, “Of Refinement in the Arts,” Essays Moral, Political and Literary (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1987), p. 271.

[10] Terry de Gunzburg, creative director of YSL Beauté, confirms: “Behind glamour, behind innovation, you have to be in love with science.” See his interview in the series “At My Vanity,” WSJ, March 9/10, 2013.

[11] D. Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 340-41. See as well Hume on the moral life as an embellishment and adornment of the person, Enquires Concerning Human Understanding and Concerning the Principles of Morals (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), p. 225.

[12] D. Hume, “Of Refinement in the Arts,” especially pp. 277-78.

[13] P. Nemo, What Is the West? (Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 2006). Cf. J. Armstrong, In Search of Civilisation (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2011).

[14] “Why Diamonds Might Not Be Forever” (William MacNamara), FT, April 27, 2010.

[15] “In Asia, Men’s Skin care Takes Off” (Jason Chow).

[16] “China’s Women Show Taste for Fast Cars and Whisky,” FT, July 5, 2011.

[17] “To the Money Born,” FT, March 30, 2010.

[18] Interestingly, Hume’s historical work served as a platform for continental Toryism, figuring in the work of de Maistre and de Bonald. See citations in Laurence Bongie’s David Hume: Prophet of the Counter-revolution (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965).

[19] J. Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Values in a Time of Upheaval (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2006), p. 139.

[20] Ibid., p. 152.

[21] Ibid., pp. 156-57.

[22] Ibid., 147; see the disturbing article by Tamara Audi on the baby business, “Assembling the Global Baby” WSJ.

[23] Ibid., p. 144-45 and n. 12.

[24] A common attitude of many theologians: For a summary of complaints and attitudes, see James Davison Hunter, “The Neo-Anabaptists,” To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (Oxford, 2010).

[25] P. Nemo, What Is the West? (Pittsburg: Duquesne University Press, 2006), chapter 4.

[26] This is correct. Please see the Kilwardby essay in my collection of essays: Disembodied Experience (pro manuscripto).

[27] Carl Schmitt thought it a disaster. Please see my introduction to his Political Romanticism (London: Transaction, 2010).

[28] J. Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Values in a Time of Upheaval, pp. 112-13, 118.

[29] Ibid., p. 161.

[30] Ibid., p. 18.

[31] It would be interesting to know if Benedict was influenced by de Lubac’s work on Proudhon.

[32] T. Rowland, “Benedict XVI, Thomism, and Liberal Culture (Part 2), Zenit, July 25, 2005.

[33] It is interesting to note that the doyen of Anglo-American moral theory, David Wiggins, identifies a break in the West’s tradition of moral thinking. In what I believe is a modern classic, Ethics: Twelve Lectures on the Philosophy of Morality, Wiggins champions David Hume against utilitarianism, and demonstrates to what degree utilitarianism deforms ordinary moral consciousness. Wiggins identifies an opposition between the civilisational tradition of Hume and the humanitarian advocacy of Bentham and Mill.

[34] Thomas Dixon has urged caution in using the word emotion arguing that a careful history of philosophy and psychological terms shows it is a creation of the Scottish Enlightenment. See his interesting book From Passions to Emotions: The Creation of a Secular Psychological Category (Cambridge, 2003).

[35] T. Aquinas, De malo, p. 508; emphasis added.

[36] Aristotle, The Art of Rhetoric (London: Penguin, 2004), p. 119, 143.

[37] Ibid., pp. 87-88.

[38] Ibid., pp. 142-43.

[39] Ibid., pp. 142-43.

[40] Ibid., p. 74.

[41] Ibid., p. 85.

[42] Ibid., p. 117.

[43] Ibid., p. 117.